CASE REPORT

Doi: 10.5578/tt.10782

Tuberk Toraks 2016;64(3):246-249

?l?mc?l domuz gribi: ?ocuk hastada? H1N1 ve Mycoplasma pneumoniae koinfeksiyonu

K Jagadishkumar KALENAHALLI1, N Arun KUMAR1, KV Ashok CHOWDARY1, MS SUMANA2

1 JSS Tıp Okulu, Pediatri B?l?m?, Mysore, Hindistan

1 JSS Medical College, Pediatrics, Mysore, India

2 JSS Tip Okulu, Mikrobiyoloji B?l?m?, Mysore, Hindistan

2 JSS Medical College, Microbiology, Mysore, Hindistan

?ZET

?l?mc?l domuz gribi: ?ocuk hastada? H1N1 ve Mycoplasma pneumoniae koinfeksiyonu

İnfluenza hastalarında en sık ?l?m nedenlerinden birisi sekonder bakteriyel infeksiyonlardır. Bu infeksiyonlara en sık neden olan patojenler Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus ve Haemophilus influenzae'dir. H1N1 olgusunda bakteriyel koinfeksiyon tanısı zor olabilir. Ancak influenza benzeri hastalık ve eşlik eden alt solunum yolu infeksiyonu belirti ve bulguları olan ?ocuklarda ş?phelenilmelidir. Bu ?alışmada yaygın pn?moni ile başvuran? ve 48 saat i?inde ?len Mycoplasma pneumoniae ve H1N1 domuz gribi koinfeksiyonu olan bir ?ocuk hastayı sunuyoruz.???

Key words: Domuz gribi H1N1,? Mycoplasma pneumoniae, koinfeksiyon, ?l?mc?l, ?ocuk

SUMMARY

Fatal swine influenza A H1N1 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae coinfection in a child

One of the most common causes of death in influenza patients is secondary bacterial pneumonia and the most common pathogens involved are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Haemophilus influenza. To diagnose co infection with bacteria in a H1N1 case can be difficult but should be strongly suspected in a child who present with influenza like illness and lower respiratory tract signs or symptoms. We report coinfection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in swine influenza A H1N1 child who presented with extensive pneumonia and expired within 48 hours.

Key words: Swine influenza A H1N1, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, coinfection, fatal, child

Geliş Tarihi/Received: 17.12.2015 - Kabul Ediliş Tarihi/Accepted: 07.01.2016

INTRODUCTION

Influenza associated coinfections with bacterial&viral infections result in significant morbidity and mortality (1). Coinfection has been found in around 30% of all seasonal influenza cases and the most common pathogens involved are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Haemophilus influenza (1,2). Secondary bacterial pneumonia is recognized as one of the most common causes of death in influenza cases (1). In addition to the common bacterial and viral infection causes other pathogens like Legionella pneumophila, Campylobacter jejuni, Dengue, HIV or tuberculosis may also be associated with influenza cases (1-4). Out of 317 pediatric deaths associated with United States pandemic H1N1 in 2009, 46 (28%) had evidence of bacterial coinfection and Staphylococcus aureus was the most common bacterial pathogen identified (5). In a study from England out of 70 paediatric deaths related to pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection bacterial coinfection was confirmed in 20% of children (6). We report coinfection of Mycoplasma pneumonia in swine influenza H1N1 child who presented with extensive pneumonia and expired within 48 hours.

CASE REPORT

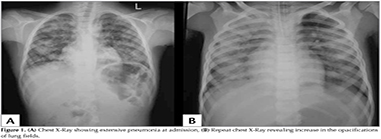

A 7-year-old previously healthy male presented with fever, cough without expectoration? since 7 days. He had recieved 2 days of co-amoxiclav tablets. There was no history of rash, sorethroat or ear discharge. On examination he was febrile (99.5?F), RR42/min, PR 96/minute and BP of 90/60 mm of Hg. Oxygen saturation at room air was 98%. There was no lymphadenopathy or conjunctival congestion. ENT examination was normal. Respiratory system examination revealed extensive crepitations all over the lung fields and bronchial breathing in the right interscapular area. Other systems examination was unremarkable. Investigations: -Hb 12.4 g/dL, TLC 7000/mm3, (Neutrophils 82%, Lymphocytes 16%), Platelet Count 2.81 lakhs/mm3 and ESR 35 mm. Chest X-Ray showed extensive pneumonia (Figure 1A]. His widal test, peripheral smear for malarial parasite, HIV serology and montoux test? were negative. He was started on Inj ceftriaxone and IV Linezolid. By 24 hours of admission child developed high degree fever (103?F) and severe respiratory distress (RR86/minute with chest retractions). Thinking of possibility of atypical pneumonia? started on azithromycin. Oxygen saturation was 90% at room air. Arterial blood gas analysis? showed a pH of 7.44, PCO2 of 30.4 mmHg, and PaO2 of 71 mmHg and HCO3 20. He was put on ventilator and after 2 hours he developed blood stained secretions from endotracheal tube. His TLC increased to 16940/mm3, neutrophils 90% and platelets 4.06 lakhs/mm3. His PT, aPTT and KFT were normal. His repeat chest X-Ray revealed increase in the opacifications of lung fields (Figure 1B). A nasopharyngeal swab for H1N1 viral testing and sputum for AFB, bacterial Gram stain and culture were obtained and started on oseltamivir along with IV meropenam. Pneumoslide-M test (Indirect immunofluorescence technique for IgM detection) which detects M. pneumoniae, L. pneumophila, Chlamidya pneumonia, Coxiella burnetii, Adenovirus, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Influenza A,B, Parainfluenza (serotypes 1,2,3) done and was positive for M. pneumoniae. His urinary antigen detection for L. pneumophila was negative. Sputum gram stain showed gram-positive cocci in pairs and few gram negative bacilli and AFB stain was negative. Repeat arteial blood gases showed metabolic acidosis and PaO2 was decreasing. Gradually he developed septic shock features and started on inotropes. ECHO showed ejection fraction of 35%. Child was not maintaining oxygen saturation even with maximum ventilator support and repeat chest X-Ray showed deterioration of lung fields. Inspite of our efforts child could not be revived and declared dead within 48 hours of admission. His blood culture was sterile. TaqMan real time Polymerase chain reaction testing of nasopharyngeal swab specimen was positive for Swine influenza A H1N1 and negative for influenza B.

DISCUSSION

One of the most common causes of death in influenza patients is secondary bacterial pneumonia (2).Throughout the world the 1918 influenza pandemic resulted in an estimated 50 million deaths and review of 8398 autopsies confirmed bacterial coinfection in nearly all deaths (7). In the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus resulted in an estimated 284.400 deaths worldwide, bacterial coinfection complicated between 18% to 34% of H1N1 cases managed in intensive care units (7). Coinfection has been found in 30% of patients with seasonal influenza (2). Out of the 155 seasonal influenza deaths, 32(38%) had evidence of bacterial coinfection and S. aureus was the most common coinfecting pathogen (5). Coinfection usually developes within the first 6.2 (range, 1.3-11.1) days of influenza infection i.e., predominantly occurs during periods of high influenza viral shedding but may occur concurrently with or shortly after influenza infection (7). The pathogens most often involved are S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and H. influenza which commonly colonize the nasopharynx (1,2,7). During the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) infection, out of 838 critically ill children 274 (33%) had clinical evidence of bacterial coinfection. Out of these 274 cases, 183(67%) had positive bacterial cultures and the most commonly isolated bacteria were S. aureus (39%) [48% isolates were methicillin resistant], Pseudomonas (16%), S. pneumonia (8%), H. influenzae (7%) and Streptococcus pyogenes (4%) (8). In Argentina, out of 199 cases of confirmed H1N1 infection 152 tested positive for at least one additional agent of potential pathogenic importance by using MassTag PCR methods which tests for 33 additional microbial agents. They include S. pneumoniae (41%), H. influenzae (68.4%), S. aureus (23%) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (4%). Along with these bacteria 20 were co-infected with another respiratory virus including RSV (A or B), rhinovirus and coronavirus (9). During 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in the United States there were 477 deaths which included 36 children. Among 23 children with culture or pathology reported results confirmed bacterial coinfections were present in 10 (43%) of them and S. aureus was the commonest bacteria isolated (10). Study from Italy identified six cases of co-infection due to L. pneumophila in H1N1 pandemic (2). Similarly H1N1 found to have coinfection with other viruses also. In addition to the common bacterial and viral infection causes other rare pathogens like C. jejuni, dengue, HIV and tuberculosis have been reported as coinfection associated with influenza H1N1 cases (1-4). To the best of our knowledge coinfection with M. pneumoniae in H1N1 case is reported for the first time.

To diagnose coinfection in a H1N1 cases can be difficult but should be suspected in a child who present with influenza like illness and lower respiratory tract signs or symptoms suggestive of pneumonia such as cough dyspnea, tachypnea, hypoxia, or signs and symptoms of sepsis (7). Our child presented with features of pneumonia and sepsis. Identification of the pathogen is also equally important because antibiotic sensitivity pattern depends on the organism isolated. To conclude H1N1 associated bacterial coinfections result in significant morbidity and mortality. Therefore high index of suspicion should be kept regarding all possible pathogenic organisms including atypical one.

REFERENCES

- Joseph C, Togawa Y, Shindo N. Bacterial and viral infections associated with influenza. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2013;7(Suppl 2):S105-S13.

- Rizzo C, Caporali MG, Rota MC. Pandemic influenza and pneumonia due to Legionella pneumophila: a frequently underestimated coinfection. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:115. doi: 10.1086/653444.

- Ormsby CE, de la Rosa-Zamboni D, V?zquez-P?rez J, Ablanedo-Terrazas Y, Vega-Barrientos R, G?mez-Palacio M, et al. Severe 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) infection and increased mortality in patients with late and advanced HIV disease. AIDS 2011;4:435-9.

- Lopez Rodriguez E, Tomashek KM, Gregory CJ, Munoz J, Hunsperger E, Lorenzi OD, et al. Co-infection with dengue virus and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;16:882-4.

- Cox CM, Blanton L, Dhara R, Brammer L, Finelli L. 2009 pandemic Influenza A (H1N1). Deaths among children-United States, 2009-2010. Clin Infect Dis 2011:52:(Suppl 1):S69-S74.

- Sachedina N, Donaldson LJ. Paediatric mortality related to pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in England: an observational population-based study. Lancet 2010;376: 1846-52.

- Chertow DS, Memoli MJ. Bacterial coinfection in influenza: a grand rounds review. JAMA 2013;309:275-82.

- Randolph AG, Vaughn F, Sullivan R, Rubinson L, Thompson BT, Yoon G, et al; Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigator's Network and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Critically ill children during the 2009-2010 influenza pandemic in the United States. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1450-8.

- Palacios G, Hornig M, Cisterna D, Savji N, Bussetti AV, Kapoor V, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae coinfection is correlated with the severity of H1N1 pandemic influenza. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e8540.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Bacterial coinfections in lung tissue specimens from fatal cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) - United States, May-August 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:1071-4.

Yazışma Adresi (Address for Correspondence)

Dr. K Jagadishkumar KALENAHALLI

JSS Medical College, Pediatrics,

MYSORE - INDIA

e-mail: jagdishmandya@gmail.com