RESEARC ARTICLE

Doi: 10.5578/tt.6903

Tuberk Toraks 2014;62(2):108-115

?kram sekt?r? ?al??anlar?n?n sigara yasas?na ili?kin g?r??leri ve i?yerlerinin de?erlendirilmesi

Sibel DORUK1, Deniz ?EL?K1, Handan ?N?N? K?SEO?LU1, ?lker ET?KAN2, ?lhan ?ET?N3

1 Department of Chest Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Gaziosmanpasa University, Tokat, Turkey

1 Gaziosmanpa?a ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi, G???s Hastal?klar? Anabilim Dal?, Tokat, T?rkiye

2 Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Medicine, Gaziosmanpasa University, Tokat, Turkey

2 Gaziosmanpa?a ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi, Biyoistatistik Anabilim Dal?, Tokat, T?rkiye

3 Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Cumhuriyet University, Sivas, Turkey

3 Cumhuriyet ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi, Halk Sa?l??? Anabilim Dal?, Sivas, T?rkiye

?ZET

?kram sekt?r? ?al??anlar?n?n sigara yasas?na ili?kin g?r??leri ve i?yerlerinin de?erlendirilmesi

Giri?: Bu ?al??mada, sigara yasa??yla ilgili ilimizde ikram sekt?r? ?al??anlar?n?n/i?verenlerin bilgi d?zeyi ve bak?? a??s?n? de?erlendirmeyi, yasan?n uygulamaya ba?lamas?ndan sonra m??teri say?s? ve gelir durumundaki de?i?iklikleri belirlemeyi ama?lad?k.

Materyal ve Metod: ?ki a?amal? olan bu kesitsel ?al??mada s?ras?yla 337 ve 310 ki?i de?erlendirilmi?tir. Sigara yasa?? uygulanmaya ba?lamadan ?nce ?ehir merkezinde 84 i?letmeyi ziyaret ettik. On sekiz ay sonra ayn? b?lgede bulunan 97 i?letme ziyaret edildi. ?al??man?n her iki a?amas?nda kat?l?mc?lar? yasa??n gereklili?i/uygulanabilirli?i hakk?ndaki g?r??leri de?erlendirildi. ?kinci a?amada gelirlerinde herhangi bir de?i?iklik olup olmad??? soruldu.

Bulgular: ?al??man?n her iki a?amas?ndaki kat?l?mc?lar?n genel ?zellikleri benzerdi. T?m kat?l?mc?lar de?erlendirildi?inde, bilgi d?zeyleri ve yasa??n gereklili?i/uygulanabilirli?i inanc?n?n zaman i?inde de?i?medi?i tespit edildi. Sigara i?meyenlerin yasan?n gereklili?i/uygulanabilirli?i inanc? daha g??l? oldu?u tespit edildi. ?al??man?n iki a?amas?na da kat?lan 38 kat?l?mc?n?n %44.7'si m??teri say?s?nda bir azalma bildirirken i?verenlerin %60 gelirlerinde art?? oldu?unu belirtmi?tir.

Sonu?: Sigara i?meyenlerin yasan?n gereklili?i ve uygulanabilirli?ine inanc? daha zay?ft?. Sonu?lar?m?za g?re sigara i?menin ilgili yasan?n uygulanmas?n? da olumsuz y?nde etkileyece?i s?ylenebilir. ??verenler yasan?n gelirlerini etkilemeyece?i konusunda bilgilendirilmelidir.

Anahtar kelimeler: Sigara, t?t?n, sigara yasas?

SUMMARY

The opinion of catering sector about the smoking ban and the evaluation of establishments

Introduction: We aimed to evaluate the knowledge and perspective of employees/employers in the catering sector in our city regarding the smoking ban, as well as to determine the changes in the number of customers and income after the bans implementation.

Materials and Methods: In this two phased cross-sectional study 337 and 310 adults were evaluated respectively. Before the smoking ban was implemented we visited 84 workplaces in city center, after 18 months later 97 workplaces were visited in the same region. In both phases, the participants' opinions about the necessity/applicability of the ban were evaluated. In the second phase, they were also asked whether they had any changes in their income.

Results: In both phases, participants' general characteristics were similar. When all participants were evaluated, we determined that their knowledge and belief in the necessity/applicability of the ban did not change over time. It was determined that non-smokers more strongly believed in the necessity/applicability of the ban. Thirty-eight participants were included in both phases; 44.7% of them reported a decrease in the number of customers, and 60% of employers reported an increase in their income.

Conclusion: The smokers were less convinced about the applicability/necessity of this ban than non-smokers. According to our results it could be said that smoking can also adversely affect implementation of the related ban. Employers should be informed that the ban will not affect their income.

Key words: Smoking, tobacco, smoking ban

INTRODUCTION

The use of cigarette and other tobacco products is an extensive public health issue, and it is the most important preventable cause of mortality in the world. One in every 10 people dies as a result of tobacco-related diseases, and in 2030, tobacco use is estimated to cause 10 million deaths worldwide (1).

In Turkey, which takes the 7th place among countries around the world in cigarette consumption, 34.6% of the adults over 18 years old are smokers (2,3). Environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) is a complex mixture of side stream and exhaled main stream smoke (4). It is well known that ETS exposure can cause significiant chronic and acute health problems in both children and adults (4). ETS exposure is the cause of death of 600 thousand non-smokers globally, and the corresponding number is estimated to be nearly 9 thousand in Turkey (5,6).

The goal of public health interventions is to improve the overall health status of the population. The recent legislative smoking ban is one of these interventions. This ban prohibits smoking in public places with the aim of protecting non-smokers from the adverse effects of ETS exposure, such as lung cancer and heart and lung diseases. Furthermore, a smoking ban in public places has been used as a strategy to reduce smoking. First, in 1975, smoking was restricted in private workplaces in compliance with clean indoor air regulations in Minnesota. As a consequence, more comprehensive programs to protect public health have been implemented in many countries (7,8,9). Turkey has joined a growing number of countries by introducing comprehensive legislation to prohibit smoking in enclosed public places. The ban entitled "Prevention and Control of Adverse Effects of Tobacco Products" which has been implemented since July 19th, 2009, prohibits smoking in defined public places such as public and private buildings that provide education, healthcare, manufacturing, trading, social, cultural, sportive, and recreational activities. It has also been instituted in confined and open areas of private restaurants, caf?s, cafeterias, pubs, public transport vehicles, pre-school education, training institutes, primary and secondary schools, and cultural and art centers (10). For the succsessful implementation of this ban, the knowledge and attitudes of catering sector employees and employers, as well as their preparations relevant to the ban are important. In the first phase of this two-phase study, we aimed to control the preparations related to this ban in the catering sector and evaluate the knowledge and opinions of the employees and employers in these workplaces in our city center regarding this ban before its implementation. In the second phase, we aimed to determine whether their opinions changed after the ban was implemented, as well as whether there were any changes in the number of customers and income of these workplaces.

Materials and methods

This study is a cross sectional study and we aimed to determine the change over the time in the knowledge and perspective of employees/employers in the catering sector in our city center. Our city, Tokat, is located in the Middle Black Sea Region of Turkey with a population of 130 thousand people living in the city center (11). Written permission for the study was obtained from Governorate of Tokat. Before initiating the study, all catering sector establishments in the city center were recorded. A list of all caf?s/cafeteria, restaurants, and pubs serving in the catering sector was obtained from the Food Control Branch Office.

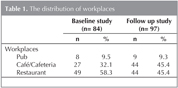

In the first phase before the smoking ban was implemented (between July 6th and 10th, 2009), we visited all workplaces in the catering sector in the city center. We administered a questionnaire survey in a total of 84 workplaces. Eight of them were pubs, 27 were caf?s/cafeterias, and 49 were restaurants. The questionnaire was applied to 59.3% (337/568) of the employees and employers who were available during the time of the study. During the survey, the participants were asked if they had been informed about the smoking ban. We also queried their opinions about the necessity and practibiliy of this ban. The preparations that had been made related to the smoking ban were recorded. All participants were asked about their smoking status, and all of the smokers were applied the Fagerstrom Nicotine Dependence Test (FTND). The cases with FTND scores greater than 5 were defined as high dependent and the others were defined as mild-moderate dependent.

In the second phase, 18 months after the implementation of the smoking ban, in addition to the 84 establishments visited in the first phase of the study we visited 13 new establishments (totally 97 establishments) in our city center. Nine of them were pubs, 44 were caf?s/cafeterias, and 44 were restaurants. The questionnaire was appllied to 310 of 420 employees and employers (73.8%) available in the workplace at that time. In addition to the items in the previous questionnaire form, the employees were asked if there had been a change in the number of customers or income, or if any customers insisted on smoking.

Statistical Analysis

Obtained data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows 18.00 statistical package program. For statistical evaluation, a chi-square test was used, and p< 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The McNemar test was used to quantify time-dependent changes in the knowledge and smoking habits of the participants. Consistencies between the results of the two phases of the study were evaluated with the significance of percent differences in dependent variable groups.

Results

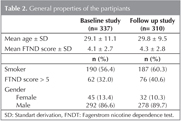

We surveyed 337 and 310 subjects in the first and second phase of the study, respectively. The distribution of establishments were shown in Table 1 and the general characteristics of the participants can be seen in Table 2. Distributions of gender, mean ages, smoking characteristics, and mean FTND scores were similar in particiants evaluated in both phases (p> 0.05) (Table 2). During this period, many employees and employers changed; thus, only 38 subjects participated in both phase of the study.

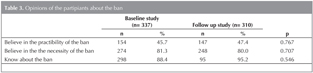

The following preparations were performed before the implementation of the smoking ban: informing of employees (96.7%), restriction of smoking among employees (86.7%), removing of ashtrays (56.7%), and hanging of warming posters (56.7%). Only 46.7% of the workplaces performed all of these preparations. It was determined that in workplaces with more than 10 employees, more preparations were performed (p= 0.032). When all participants were evaluated, it was determined that the knowledge and opinions of the participants' did not change over time (Table 3).

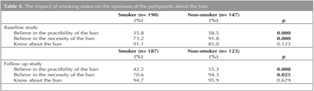

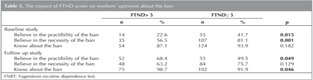

In both phases of the study, it was determined that non-smokers more strongly believed the necessity and applicability of the ban than the smokers (Table 4). There was no difference between smokers and non-smokers in terms of being informed about the ban. The impact of FTND scores for being informed about the ban and opinions on the ban can be seen in Table 5. In both phases of the study, high dependent smokers more strongly believed in the necessity and applicability of the ban than the others. Thirty of 38 participants who were enrolled in both phases of the study were asked about how their opinions and their smoking habits had changed over time. Four smokers quit smoking, and two of the high nicotine dependence smokers switched to the low-moderate category. The opinion of 25 (83.3%) the participants on the necessity of the ban had not changed, and 22 (73.3%) of them had not changed their opinion about the applicability of the ban either. A small number of participants began to think that the ban was unnecessary (n= 5) and inapplicable (n= 8).

Nineteen (50.0%) of the 38 participants in both phases indicated that there had been no change in the number of customers, while the others reported an increase (n= 2; 10.5%) or a decrease (n= 17; 39.5%). Twelve (60.0%) of 20 employers indicated an increase in their income levels. Three hundred and seven participants in the second phase of the study responded to the question, "Do you ever have any customers that insist on smoking?", and 156 (50.8%) of them reported that some customers insisted on smoking despite the ban.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the opinion of catering sector employees and employers about the smoking ban in enclosed areas, before and after the ban's implementation, in a city with a population of approximately 130 thousand. After evaluation of all participants' opinions, it was determined that their opinions on the applicability and necessity of this legislative ban did not significantly change over time. In addition, of those participants who were included in both phases of the study, the number who believed in the unnecessity and inapplicability of such a ban increased over time. Particularly among high nicotine dependent smokers, the belief in the applicability of the ban was lower than the others.

As diseases are discovered that develop as a direct result of passive smoking, various interventions that prohibit smoking in public places are being implemented. Globally, in many countries, it has been accepted that pasivve smoking can be prevented by banning smoking in restaurants (12). Smoking has been forbidden in Turkey since July 19, 2009, with smoking bans instituted in 5727 private recreation workplaces such as restaurants, caf?s, cafeterias, and pubs (10). These bans represent just of several intervention strategies that have been used to reduce smoking and prevent ETS exposure. Besides preventing ETS exposure, smoking bans in public places represent one of several intervention strategies that have also been used to reduce smoking (13). The literature documents report a relationship between smoking bans in public places and a decrease in smoking prevalence (7,8). The comprehensive tobacco control programme introduced in Taiwan in 2009 was associated with a reduction in adolescent smoking (14). In Turkey, cigarette sales increased between over the years. However, it has tended to decrease in recent years. The amount of cigarettes that was sold in the first four months of 2010 was approximately 25% lower than the same interval in 2009 (15).

In various surveys that were carried out before the implementation of the ban, it was determined that most of the participants supported this ban. In our country, a survey carried out by the Turkish Society of Public Health Specialists (TSPHS) in 2008, indicated that 87.5% of the non-smokers, and 55.9% of the smokers supported the smoking ban (16). In the study performed by the Ministry of Health of Turkish Rebuplic, it was reported that 93.3% of participants supported this ban (17). Another study conducted by TSPHS determined that 86.9% of the employees in the catering sector were convinced that this ban was necessary, while the corresponding rates in smokers and non-smokers were 86.5%, and 91.3%, respectively (18). Jiang et al. reported the percentage of respondents supporting a total smoking ban in restaurants was 17% among managers, 13.4% among employees, and non-smokers were more likely to support a total smoking ban (19). In Lebanon among students non-smokers strongly supported non-smoking policy in public places compared with smokers while smaller percentages reported that the ban would help in reducing smoking to a large extent or it would help smokers quit (20).

In both phases of our study, nearly 80% of all participants asserted that they believe in the necessity of this ban. However, the corresponding rate in both phases of the study was more than 90% in smokers. Despite this high rate of participants' belief in this ban's necessity, only half of the participants were convinced of its applicability, which is an interesting but literarily compliant outcome (17). These results can be related to the high rates of smoking in our country (2,3,5). Besides, despite the ban, the presence of the customers that insist on smoking supported this conclusion.

In the national study including individuals over 15 years of age, the Ministry of Health of the Turkish Republic in 2008 reported that 89.7% of participants were informed about this new ban, which is similar to our results (17). However in Tachfouti et al.'s study, only one third of the participants knew about the antismoking legislation and approximataly half of these participants were aware of the ban on smoking in public areas (21). In our study, high rate of awareness may be considered a positive result in terms of the applicability of the ban. Smoking in public places like restaurants, cafeterias, beerhouses, and pubs threatens the health of employees and customers. A smoke-free work environment is necessary for the health of employees. Fidan et al. reported that mostly non-smoking workers had the desire to work in a smoke-free workplace and supported the proposal of a new smoking ban in all workplaces (22). With regard to policy restrictions, former smokers and those who have never smoked support total workplace bans on smoking, while tobacco users want designated smoking areas (23). In our study, it was determined that non-smokers believe in the necessity and applicability of the smoking ban more than smokers, also smokers with higher FTNDs scores were less convinced about the necessity and applicability of this ban. The higher prevalence of smoking among participants, and increased nicotine dependence in particular, seems to limit the ability to successfully implement the ban. Therefore, we believe that smoking cessation could contribute to the prevention of smoking-related diseases, protect the health of non-smokers, and also increase compliance with the ban.

In Emmons et al.'s study a smaller sized workplace was defined as a predictor of more restrictive ETS policies (24). Several studies have found that smaller worksites are much less likely to report having a restrictive policy than are larger worksites (25,26,27,28). In another study, it was indicated that restaurants with fewer than 200 seats were more likely to support a total smoking ban (19). In our study, we determined that in larger workplaces with more than 10 employees, more preparations related to the ban were performed than in other establishments. Increasing public support for smoking bans was reported based on independent population surveys conducted before and after the legislation takes effect (29,30,31). Conversely, in our study, participants' belief in the necessity of the ban decreased at a rate of 16.7% over time. In a survey in Norway, it was determined that 54% of the population supported the smoking ban. In the study performed by Braverman et al. restaurant employers supported the ban at a similar rate. The rate of the employees who supported the ban was higher in our study. Braverman et al. indicated that bartenders supported the ban less than restaurant employees. In our study, we determined that in all kinds of establishments, employees supported the ban at similar rates (32,33). In Ireland, a decrease in the consumption of tobacco products and the frequency of smoking among bartenders suggested that smoke-free workplaces can effectively control tobacco use (34). In our study, the number of the participants we evaluated in terms of their smoking habits is low, but the rate of smoking and nicotine dependence decreased after the ban was implemented.

In the first phase of the study performed just before the smoking ban's implementation, as one of the important outcomes of our study, we determined that only half of the workplaces made preparations for the ban. In the future, intensifying the controls related to the ban will contribute to ensuring the necessary regulations are followed. The most frequently performed preparations were restricting smoking among staff and informing them about the ban. The reason that the preparations related to the customers, such has putting up warning posters on the wall and removing ashtrays from the tables, were less frequent is that the employers fear losing money by doing so. Therefore, informing employers that they will not lose income by engaging in such practices may improve their adherence to such preparations. In addition to its beneficial effects on health status, the impact of the smoking ban on an establishment's income has also been discussed. Many studies have been carried out to determine the economic effects of this ban. Results from studies examining the legislation's financial impact appear mixed. The common opinion, however, is that this smoking ban affects establishments negatively (35,36).

However, several investigations indicated an increase or at least stabilization in their income because of the increased number of non-smoking customers (37,38). Lund et al. determined a large (%28.2), or some (28.2%) reduction in the number of the customers, some (5.8%), or large (2.1%) increases in patronage, and a large percent remained unchanged (35.6%). The participants in our study reported a lower rate of decrease and a higher rate of increase in the number of customers than Lund et al.'s study (39). Another study examining the legislation's impact on customer visits revealed no overall effect (34). Hilton et al. reported that the rate of the participants who thought that this ban would adversely effect the establishments was 50.5% before the ban's implementation and 19.2% after the implementation (40). Pursell et al. found that the rate of individuals who did not think the ban would adversely affect the establishments was 28.2% before and 25.5% after this ban (41). In both surveys, a decrease in the frequency of unfavorable opinions was observed. The survey carried out by Pursell et al. revealed that before and after the implementation of this ban, 40.9%, and 25.9% of the responders, respectively, did not believe the ban would decrease the number of customers (41). In George, Gvinianidze et al. reported that part of owners/staff of cafes and restaurants don't support any type of ban or restriction, because of their fear to loose smoker clients (42). In our study, 40.0% of the participants who were included both phases reported a decrease in the number of customers, but more than half of the employers reported an increase in their income.

A short time has passed since the ban was implemented, and the establishments were stil not adequately prepared at the time of our study. This result can be due the belief that the ban may have limited applicability. The employees and the employers should be informed about performing the preparations related to the ban without having worry about incurring economic loss, and the relevant agencies should make the necessary inspections. Despite the smoking ban, the presence of customers who insist on smoking supports the participants' unfavorable opinions of the smoking ban and its limited applicability. The decreasing smoking rate we found in this study is encouraging, but further investigations are needed that consecutively evaluate a larger number of participants. The increase in the number of the participants who believe the ban is inapplicable may be due to deficiencies in the inspections or criminal proceedings. In addition, in order to determine the economic effects of this ban, further studies need to be conducted that include objective economic data.

One interesting finding in our study is that the smokers with greater dependence on nicotine were less convinced about the applicability of this ban. Along with the multiple adverse effects of smoking, it can also adversely affect the legal arrangement that aims to protect non-smokers and reduce smoking.

CONFLICT of INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- The World Health Report 1999: Making a difference. Geneva: World Health Organization. [cited 2010 April]; Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/1999/en/whr99_en.pdf

- WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER Package. Geneva, Switzerland. [cited 2010 June]; Available from: http:// www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/en/

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health. National Tobacco Control Program and Activity Plan 2008-2012. Ankara 2008. [cited 2011 December] Available from: http://www.saglik.gov.tr/TSHGM/belge/1-6961/ulusal-tutun-kontrol-programi-ve-eylem-plani- 2008-2012.html

- California Environmental Protection Agency. Health effects of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Final report. California environmental protection agency office of environmental health hazard assessment, 1997. [cited 2010 June] Available from: http://oehha.ca.gov/pdf/chapter1.pdf

- World Health Organization Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2009. Implementing smoke-free environments. [cited 2011 December] Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563918_eng_full.pdf

- Karlikaya C, Oztuna F, Solak ZA, Ozkan M, Orsel O. Tobacco control. Turkish Thoracic Journal 2006;7(1):51-64.

- Cesaroni G, Forastiere F, Agabiti N, Valente P, Zuccaro P, Perucci CA. Effect of the Italian smoking ban on population rates of acute coronary events. Circulation 2008;117(9):1183-8.

- Frieden TR, Mostashari F, Kerker BD, Miller N, Hajat A, Frankel M. Adult tobacco use levels after intensive tobacco control measures: New York City, 2002-2003. Am J Public Health 2005;95(6):1016-23.

- Collins NM, Shi Q, Forster JL, Erickson DJ, Toomey TL. Effects of clean indoor air laws on bar and restaurant revenue in Minnesota cities. Am J Prev Med 2010;39(6):10-15.

- T?t?n mamullerinin zararlar?n?n ?nlenmesine dair kanunda de?ifliklik yap?lmas? hakk?nda kanun. Resmi Gazete Date: 28 January 2008 Number: 26761.

- [cited 2010 Macrh]; Availablae from: http://www.tokat.bel.tr/icerik.asp?id=13

- Karlikaya C. Smoking restrictions in restaurants. Tuberk Toraks 2005;53(4):407-9.

- H?jgaard B, Olsen KR, Pisinger C, T?nnesen H, Gyrd-Hansen D. The potential of smoking cessation programmes and a smoking ban in public places: Comparing gain in life expectancy and cost effectiveness. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(8):785-96.

- Huang SL, Lin IF, Chen CY, Tsai TI (2013). Impact of tobacco control policies on adolescent smoking: findings from Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Taiwan, doi: 10.1111/add.12259. [Epub ahead of print]

- K?resel yetiflkin t?t?n araflt?rmas?. [cited 2011 December] Available from: http://www.havanikoru.org.tr/Docs_Tutun_Dumaninin_Zararlari/KYTA_Kitap_Tr.pdf

- Kapal? ortamlarda sigara i?ilmesinin yasak olmas? hakk?nda g?r?fller. HASUDER Raporu, Ankara, May?s, 2008. [cited 2009 October] Available from: http://www.dumansizhavasahasi.org.tr/Docs Sunumlar/Tutun Kontrolu Yasas? ve Ulke ?rnekleri.pdf

- Yeni t?t?n kontrol yasas? ve iliflkili uygulamalar konusunda 15 yafl ve ?zeri kiflilerin bilgi, g?r?fl ve davran?fllar?. [cited 2009 October] Available from: http://www.havanikoru.org.tr/Docs_Arastirmalar/Kanun Hakkinda Vatandaslar?m?-z?n Bilgi ve Farkindalik Duzeyi Arastirmasi.pdf

- ?zcebe H, Boztafl G, ??ray S, Demirtafl B, Derin ME, Din?soy F, Dolgun ?. 06.10.2008-15.10.2008 tarihleri aras?nda K?z?lay Konur ve Selanik sokaklar?nda bulunan kafe ve restoranlardaki ?al?flan ve m?flterilerin 4207 say?l? kanun hakk?ndaki bilgileri, yasaya bak?fl a??lar? ve kapal? ortam ?l??mleri. [cited 2009 October] Available from: http://www.hasuder.org/sigara/kizilayda.pdf

- Jiang L, Sriplung H, Chongsuvivatwong V, Li T, Xiao Y. Attitudes towards a smoking ban in restaurants of managers, employees and customers in Kunming City, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2010;41(5):1258-66.

- Chaaya M, Alameddine M, Nakkash R, Afifi RA, Khalil J, Nahhas G. Students' attitude and smoking behaviour following the implementation of a university smoke-free policy: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013;3(4).

- Tachfouti N, El RK, Berraho M, Benjelloun MC, Slama K, Nejjari C. Knowledge and attitude about antismoking legislation in Morocco according to smoking status. East Mediterr Health J 2011;17(4):297-302.

- Fidan F, Sezer M, Unlu M, Kara Z. Knowledge and attitude of workers and patrons in coffeehouses, cafes, restaurants about cigarette smoke. Tuberk Toraks 2005;53(4):362-70.

- Mikanowicz CK, Fitzgerald DC, Leslie M, Altman NH. Medium-sized business employees speak out about smoking. J Commun Health 1999;24(6):439-50.

- Emmons KM, Thompson B, McLerran D, Sorenson G. The relationship between organizational characteristics and the adoption of workplace smoking policies. Health Educ Behav 2000;27(4):483-501.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: 1992 National Survey of Worksite Health Promotion Activities: Final Report (Pub. No. PB93-500023). Washington, DC, Government Printing Office, 1993.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service (1993). 1992 National Survey of Worksite Health Promotion Activities: Summary American Journal of Health Promotion 1993;7:452-64.

- American Cancer Society: Health Promotion in Small Business: A Statewide Report. Unpublished report, Framingham, MA, American Cancer Society Massachusetts Division, 1992.

- Pierce JP, Evans N, Farkas AJ, et al. Tobacco Use in California: An Evaluation of the Tobacco Control Program, 1989-1993. La Jolla, University of California, San Diego, 1994.

- Donnelly P, Whittle P. After the smoke has cleared reflections on Scotland's tobacco control legislation. Public Health 2008;122:762-6.

- Gorini G, Chellini E, Galeone D. What happened in Italy? A brief summary of studies conducted in Italy to evaluate the impact of the smoking ban. Ann Oncol 2007;18:1620-2.

- Tang H, Cowling DW, Lloyd JC, Rogers T, Koumjian KL, Stevens CM, et al. Changes of attitudes and patronage behaviors in response to a smoke-free bar law. Am J Public Health 2003;93:611-7.

- Braverman MT, Aar? LE, Bontempo DE, Hetland J. Bar and restaurant workers' attitudes towards Norway's comprehensive smoking ban: a growth curve analysis. Tob Control 2010;19(3):240-7.

- Lund KE. The introduction of smoke-free hospitality venues in Norway. Impact on revenues, frequency of patronage, satisfaction and compliance. SIRUS series No. 2/2006. Oslo: The Norwegian Institute for Alcohol and Drug Research, 2006.

- Mullally BJ, Greiner BA, Allwright S, Paul G, Perry IJ. The effect of the Irish smoke-free workplace legislation on smoking among bar workers. Eur J Public Health 2009;19(2):206-11.

- Adda J, Berlinski S, Machin S. Short-run economic effects of the Scottish smoking ban. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36(1):149-54.

- MacKintosh AM, Holme I, Hastings G, Hassan L, Hyland A, Higbee C. (for the CLEAN Collaboration) 2008. The ITC Ireland/Scotland Project: The International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey (ITC). Smokefree Agreement Number Project 02128 (NH5005.003R). Stirling: Institute for Social Marketing, University of Stirling.

- Biener L, Fitzgerald G. Smoky bars and restaurants: Who avoids them and why? J Public Health Manag Pract 1999;5(1):74-8.

- Biener L, Siegel M. Behavior intentions of the public after bans in restaurants and bars. Am J Public Health 1997;87(12):2042-4.

- Lund I, Lund KE. Post-ban self-reports on economic impact of smoke-free bars and restaurants are biased by pre-ban attitudes. A longitudinal study among employees. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7):776-9.

- Hilton S, Semple S, Miller BG, et al. Expectations and changing attitudes of bar workers before and after the implementation of smoke-free legislation in Scotland. BMC Public Health 2007;7:206.

- Pursell L, Allwright S, O'Donovan D, et al. Before and after study of bar workers' perceptions of the impact of smoke-free workplace legislation in the Republic of Ireland. BMC Public Health 2007;7:131.

- Gvinianidze K, Bakhturidze G, Magradze G. Study of implementation level of tobacco restriction policy in cafes and restaurants of Georgia. Georgian Med News 2012;206:57-63.

Yaz??ma Adresi (Address for Correspondence)

Dr. Sibel DORUK

Gaziosmanpa?a ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi,

G???s Hastal?klar? Anabilim Dal?,

TOKAT - TURKEY

e-mail: sibeldoruk@yahoo.com