Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis; characteristics of 11 cases

Koray AYDO?DU1, Ersin G?NAY2, G?kt?rk FINDIK1, Sibel G?NAY3, Yetkin A?A?KIRAN4,

Sadi KAYA1, Nurettin KARAO?LANO?LU1, ?rfan TA?TEPE5

1 Atat?rk G???s Hastal?klar? ve G???sCerrahisi E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi. G???sCerrahisi B?l?m?, Ankara,

2 Afyon Kocatepe ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi, G???s Hastal?klar? Anabilim Dal?, Afyonkarahisar,

3 Afyonkarahisar Devlet Hastanesi, G???s Hastal?klar? Klini?i, Afyonkarahisar,

4 Atat?rk G???sHastal?klar? ve G???sCerrahisi E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi, Patoloji B?l?m?, Ankara,

5 Gazi ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi, G???s Cerrahisi Anabilim Dal?, Ankara.

?ZET

Pulmoner Langerhans h?creli histiyositozis; 11 olgunun ?zellikleri

Giri?: Pulmoner Langerhans h?creli histiyositozis (PLHH) gen? pop?lasyonun nadir g?r?len bir hastal???d?r. Hastalar?n hemen hemen hepsi sigara i?icisidir. Bu ?al??mada, PLHH tan?l? 11 olgunun ?zelliklerini, tan?s?n?, tedavisini ve prognozunu de?erlendirmeyi ama?lad?k.

Materyal ve Metod: Patolojik olarak PLHH tan?s? konulan 11 olgu serisi tarand?. Olgular?n ortanca ya?? 35 (19-51) ve erkek/kad?n oran? 5/6 idi. Hastalar?n hepsi semptomatikti. En s?k semptomlar dispne (%81.8) ve kuru vas?fl? ?ks?r?k (%72.7) idi. Ortalama semptom s?resi 10.8 ay idi. ?ki olgu d???nda t?m olgular (%81.8) aktif sigara kullan?c?s?yd?. T?m olgular?n pasif t?t?n maruziyeti mevcuttu.

Bulgular: Bilateral kistik g?r?n?m (n= 9, %81.8), interstisyel bulgular [septal ve peribronkovask?ler kal?nla?ma (%72.7) ve nod?ler patern (%54.5)] en s?k radyolojik bulgulard?. Spontan pn?motoraks iki olguda saptand?. Hastalara cerrahi biyopsi (%90.9) veya transbron?iyal biyopsi (%9.1) ile tan? konuldu. Sigara b?rakma ve imm?ns?presif tedavi (metilprednizolon) hastalara ?nerilen tedavilerdi. Ortalama takip s?resi 5.40 ? 1.78 y?l idi. Semptomlar sigara b?rakma veya metilprednizolon tedavisiyle geriledi. Olgulardan sadece bir tanesi takipte tekrarlayan pn?motoraks nedeniyle hastaneye ba?vurdu.

Sonu?: PLHH geli?imden aktif sigara kullan?m? yan?nda pasif i?icilik de sorumludur. PLHH tedavisi i?in birka? ?neri d???nda tam bir fikir birli?i mevcut de?ildir. Bu nadir hastal???n patogenezinin anla??lmas?yla yeni tedavi y?ntemleri geli?ebilecektir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Pulmoner Langerhans h?creli histiyositozis, sigara i?me, pasif i?icilik, sigara b?rakma, metilprednizolon.

SUMMARY

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis; characteristics of 11 cases

Koray AYDO?DU1, Ersin G?NAY2, G?kt?rk FINDIK1, Sibel G?NAY3, Yetkin A?A?KIRAN4,

Sadi KAYA1, Nurettin KARAO?LANO?LU1, ?rfan TA?TEPE5

1 Ataturk Chest Diseases and Thoracic Surgery Training and Research Hospital,

Department of Thoracic Surgery, Ankara, Turkey,

2 Department of Chest Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Afyon Kocatepe University, Afyonkarahisar, Turkey,

3 Afyonkarahisar State Hospital, Chest Disease Clinic, Afyonkarahisar, Turkey,

4 Ataturk Chest Diseases and Thoracic Surgery Training and Research Hospital, Department of Pathology,

Ankara, Turkey,

5 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Gazi University, Faculty of Medicine, Gazi University,

Ankara, Turkey.

Introduction: Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) is a rarely seen disease of younger population. Almost all of the patients were smoker. In this study we aimed to evaluate the characteristics, diagnosis, treatment modalities and prognosis of 11 cases with PLCH.

Materials and Methods: We retrospectively reviewed our case series of eleven patients who were pathologically diagnosed as PLCH. The median age was 35 years (19-51) and male to female ratio (M/F) was 5/6. All of the patients were symptomatic. The most common symptoms were dyspnea (81.8%) and dry cough (72.7%). Mean duration of the symptoms was 10.8 months. All patients except two of them were smoker (81.8%). All patients were also passive smokers.

Results: Bilateral cystic appearance (n= 9, 81.8%), interstitial findings [septal and peribronchovascular thickening (72.7%) and nodular pattern (54.5%)] were common radiological findings. Spontaneous pneumothorax was present in two cases. All patients were diagnosed with surgical biopsies (90.9%) or transbronchial parenchymal biopsy (9.1%). Smoking cessation (81.8%) and immunosupression therapy (methylprednisolone) were the treatment modalities. Mean follow-up period was 5.40 ? 1.78 years. Generally, symptoms were improved with smoking cessation or methylprednisolone therapy. One patient was readmitted to our clinic with recurrent pneumothorax. In conclusion, it should be kept in mind that passive smoking is also responsible in the pathogenesis of PLCH.

Conclusion: Exact consensus for PLCH treatment was not present except a few recommendations. In the future, with the understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease, new therapeutic agents will be discovered for this rare condition.

Key Words: Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, smoking, passive smoking, smoking cessation, methylprednisolone.

Tuberk Toraks 2013; 61(4): 333-341 • doi:10.5578/tt.5944

Geli? Tarihi/Received: 02/06/2013 • Kabul Edili? Tarihi/Accepted: 28/07/2013

Introduction

The histiocytic disorders are uncommon diseases characterized by abnormal infiltration of certain organs by cells derived from monocyte/macrophage or dentritic cell lineage (1,2,3). The classification of the clinical patterns of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is based on the number of organs involved (1). Single organ (bone, lung, pituitary gland or skin) involvement of LCH (eosinophilic granuloma and primary pulmonary histiocytosis) usually follows benign course and can regress spontaneously (1,3,4). Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (PLCH) is a relatively uncommon granulomatous disorder characterized by uncontrolled proliferation and infiltration of Langerhans cells (LCs) in the lung (1,5). It has been associated with cigarette smoking and is more common in young adults. The pathogenesis of PLCH is unclear (1,2,5). In the literature, there is limited number of studies investigating the characteristics and prognosis of PLCH. In the present study, we evaluated the characteristics, diagnosis, treatments modalities and prognosis of 11 cases of PLCH.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed our case series of eleven patients who were pathologically diagnosed for PLCH between January 2001 and January 2011. Characteristics, symptoms and smoking habits of the patients, radiological [chest X-ray (CXR) and thorax computed tomography (CT) and high resolution computed tomography (HRCT)] findings, diagnostical procedures (bronchoscopy, transbronchial biopsy, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) findings and types of surgical procedures), treatment options and prognosis/relapses were noted. The CXR, thorax CT, HRCT and fiberoptic bronchoscopy were performed. All cases were diagnosed with pathological examinations.

Results

The median age was 35 years (19-51 years) and male to female ratio (M/F) was 5/6. All of the patients were symptomatic. Complaints of the patients were as follows; dyspnea (n= 9, 81.8%), dry cough (n= 8, 72.7%), chest pain (n= 3, 27.3%), fatigue (n= 3, 27.3%), weight loss (n= 2, 18.2%), pneumothorax (n= 2, 18.2%), clubbing (n= 2, 18.2%), fever (n= 1, 9.1%), haemoptysis (n= 1, 9.1%), diabetes insipidus (n= 1, 9.1%) and pectus carinatum (n= 1, 9.1%). Mean duration of the symptoms till diagnosis was 10.8 months (2-36 months). Only 2 (18.2%) patients were non-smoker and mean cigarette consumption was 17.6 pack-years (6-30 pack-years). All patients were also passive smokers.

The CXR findings were as follows; bilateral cystic appearance (n= 9, 81.8%), bilateral reticular and/or nodular infiltration (n= 6, 54.5%), pneumothorax (n= 2, 18.2%) and costaphrenic sinus involvement (n= 1, 9.1%) (case #8). Predominantly middle zone involvement was observed (middle zone/upper zone/lower zone= 9/5/1).

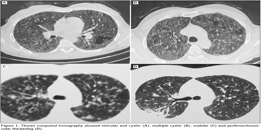

Thorax CT and HRCT findings were bilateral multiple cystic lesions (n= 9, 81.8%), interstitial thickening (septal and/or peribronchovascular) (n= 8, 72.7%), nodular pattern (n= 6, 54.5%), groud-glass opacity (n= 2, 18.2%), pneumothorax (n= 2, 18.2%), honeycombing appearance (n= 1, 9.1%) and pleural effusion (n= 1, 9.1%) (Figure 1).

Pulmonary function test results of nine patients revealed restrictive pattern in 3 (33.3%) patients, obstructive pattern in 2 (22.2%) patients, mixed pattern in 2 (22.2%) patients. Normal pulmonary function test result was present in two PLCH patients (22.2%).

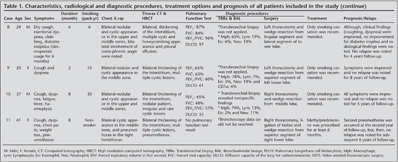

Diagnostic procedures that were applied to our patients were flexible bronchoscopy, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transbronchial parenchymal biopsy, and wedge biopsy via video-assisted thoracoscopy or thoracotomy. Fiberoptic bronchoscopic results of 7 patients were achieved. BAL results of seven patients revealed as follows (Mean ? SD); macrophages (%): 76.28 ? 8.20, lymphocytes (%): 11.57 ? 5.22, neutrophiles (%): 8.43 ? 4.20 and eosinophiles (%): 3.86 ? 1.57. CD1a results for Langerhans cells (%) were studied in 4 samples of patients (case #1, 2, 5 and 9) (Table 1).

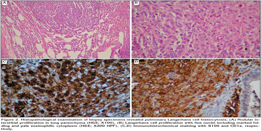

Wedge biopsies that were taken via VATS were diagnostic in two patients (18.2%) and wedge biopsies taken via thoracotomy were diagnostic in 8 (72.7%) patients. Transbronchial parenchymal biopsy was successful in diagnosis of 1 (9.1%) patient (Figure 2).

Only smoking cessation was suggested to 9 (81.8%) patients. However, additional therapy of methylprednisolone was initiated for uncontrolled symptoms in one of these patients. Two (18.2%) of patients who were nonsmoker were treated only with methylprednisolone for six months.

Mean follow-up of ten patients was 5.40 ? 1.78 years. Only one patient (case #4) did not come to his follow-up visits after 6 months of his diagnosis. Generally, symptoms were improved with smoking cessation or methylprednisolone therapy. One patient (case #11) was readmitted to our clinic with relapse of second pneumothorax.

Discussion

In this study, we described the clinical-radiological findings, BAL characteristics, diagnostic procedures, treatment options and prognosis of eleven patients with PLCH. Nine of 11 patients was smoker. Although ten patients were diagnosed via surgical procedures, only one patient was diagnosed via transbronchial lung biopsy. Only three patients were needed to treat with methylprednisolone.

Pulmonary involvement with LCH can be observed in patients of any age (6). PLCH in adults is a rare idiopathic parenchymal disease of the lung and commonly detected in adults with the smoking history (1). It is known that more than 90% of patients with PLCH are current smoker or ex-smoker (6,7,8). The pathogenic mechanisms that link tobacco smoke exposure to these disorders have not been clarified (7). Moreover, development of PLCH in nonsmokers especially in childhood period suggests that second-hand smoking play a role in the pathogenesis (2,6). PLCH mainly affects young adults with a peak frequency in the third to fourth decades (1,2,4). Although marked male predominance was initially reported, gender differences were disappeared in recent studies which may be due to increased cigarette smoking habit in female (1,4,6,7,9). In this study median age was 35 years (min-max: 19-51 years) and male to female ratio (M/F) was 5/6 (smoker male to female ratio was 4/5). The ratio of patients who smoke cigarette (81.8%) was lower than that was reported in the literature. This result may lead to consider the effect of passive smoking on pathogenesis of PLCH.

Although, in pediatric ages, pulmonary involvement is reported as the part of multisystemic LCH, single system disease (PLCH) in adult population was reported more than 80% of the patients (10,11). Symptoms show variability according to organ involvements. Clinical symptoms of patients with PLCH is miscellaneous (1,6). Approximately one fourth of the patients are asymptomatic (1,8). Persistent dry cough, exertional dyspnea, and chest pain are main symptoms (1,6,7,11). Pneumothorax is a complication resulting from the rupture of subpleural cystic lesions in 10-20% of the cases (1,6). Clubbing of the fingers is extremely rare finding in PLCH. Diabetes insipidus (5% of cases), bone lesions (> 20%) and skin lesions are the most common extrapulmonary findings (1,12,13). In our study, the most common symptoms were dyspnea (81.8%) and dry cough (72.7%) as reported in the literature. Pneumothorax was occurred in 18.2% of the cases and recurrent pneumothorax was diagnosed in only one patient. Diabetes insipidus was sole extrapulmonary presentation in this study. Although, it is a rare finding, clubbing was present in two patients.

The CXR is almost always abnormal. Reticulonodular infiltrates are predominant findings in early disease stage whereas cystic lesions are more dominant in advanced stage. Radiological changes in advanced stage can be difficult to differentiate from cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Nodular or reticulonodular involvement is typically diffuse. Relative sparing of the lower lung fields and costo-phrenic angle is characteristic in adults (2,14). However, chest radiography in pediatric PLCH is almost always associated with involvement of the lower lung zones and the costo-phrenic angles (1,2,14,15). In our study, major CXR findings were bilateral cystic lesions (45.4%), bilateral nodular infiltrations (18.2%) and mixed pattern (36.4%). While, middle zone (81.8%) was predominant involved zone in the study population, lower zone and costo-phrenic sulci involvement was present in one patient.

In several studies, characteristic distribution of nodules, cystic lesions was upper and middle lung fields in thorax CT and HRCT (1,2,16-19). HRCT is an important tool for the physicians in choosing an optimal site for bronchoscopic transbronchial parenchymal biopsy, BAL and open biopsy. While pulmonary nodules are commonly found in early stages, cystic lesions are more frequently seen in advanced disease stages (2,17-19). In this paper, major tomographic findings were bilateral multiple cystic lesions (81.8%), interstitial thickening (72.7%) and nodular pattern (54.5%).

Pulmonary function tests are normal up to 20% of patients (2,11). Restrictive pattern is more commonly seen in earlier stages of disease, while obstructive pattern is became predominant in advanced stages (2,13,20). At least 70% of patients have low carbon monoxide diffusion capacity (DLCO) which is the most common abnormality in PLCH (2,11,21). In this study, restrictive pattern (33.3%) was found to be more prevalent. As in the literature, 22.2% of all patients had normal pulmonary function test. DLCO was decreased in 63.6% of patients which was slightly lower than the literature.

Histopathological diagnosis with lung biopsies is needed for definitive diagnosis of PLCH. Transbronchial parenchymal biopsies obtained via fiberoptic bronchoscopy state the exact diagnosis in an approximately 15-40% of patients (2,22). Besides, BAL is also suggested diagnostic method performing to all patients underwent bronchoscopy. Detection of more than 5% CD1a (+), a cell surface marker for LCs, in BAL fluid with appropriate clinical symptoms and radiological findings (HRCT) are suggestive for PLCH (1,2,21). This test is problematic, however, because increased level of CD1a-positive cells can be identified in the BAL fluid of smokers without evidence of interstitial lung disease (2). Additional surface markers, such as an antibody against langerin (CD207), may improve the diagnostic utility of BAL in the diagnosis of PLCH (21,23). In this study, histopathological examination of transbronchial biopsy of lingular segment in one patient revealed the diagnosis of PLCH. CD1a was evaluated in 4 out of 7 patients whom BAL was performed. None of the results was greater than 5%.

In the case of uncertainty of making diagnosis, surgical lung biopsies by VATS or open thoracotomy may be required to make a definite diagnosis of PLCH by demonstrating the presence of the specific histopathological appearance (2,21). The diagnostic histological finding is LCs and the number of cells vary according to the disease stages (6,12). In our study, to diagnose the disease, wedge resections by thoracotomy and VATS were performed to 8 and 2 patients, respectively.

There is not an exact treatment guideline for PLCH management. A few recommendations are reported concerning to treatment of adult patients with PLCH (7,21). An important step of the treatment of patients with PLCH is smoking cessation. Smoking cessation alone may lead to improvement and marked resolution of the disease, so, it should be strongly encouraged (7,21). Although, corticosteroid treatment is also a kind of recommended therapeutic management, evidence of benefit is unclear (7,11,12,21). Especially, corticosteroid usage (0.5-1 mg/kg/day for 6-12 months) was suggested to progressive or the symptomatic patients with nodular lesions on HRCT (1,6,21). Other chemotherapeutic agents including vinblastin, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, etoposide may be preferred especially in the case of multiorgan involvement or unresponsiveness to steroid treatment (2,6,21,24). Lung transplantation is suggested when severe respiratory failure was occurred. Genetic, monoclonal antibody and cytokine treatments are the future potential treatment options in PLCH (2,21,25). In our study, all patients except two were current smokers. Passive smoking was noted in all patients. Only smoking cessation was suggested to current smokers. Clinical and radiological improvement was achieved in 8 patients. Steroid therapy was administered to three patients.

Persistent systemic symptoms, recurrent pneumothorax, extrathoracic lesions, impairment in pulmonary functions (decrease in DLCO, FEV1/FVC and increase in residual volume/total lung capacity), costo-phrenic angle involvement, and younger and advanced ages were reported as worse prognostic factors (1,2,4,6,11, 24).

In conclusion, PLCH is an extremely rare benign disease. The present study is the first national case series evaluating the symptoms, radiological findings, diagnostic and treatment approaches for PLCH in our country. To our knowledge, there is not an exact consensus with respect to the guidelines on the treatment of PLCH. We believe that this article will add to the literature in the context of treatment options and treatment outcomes of PLCH. In the future, with the understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease, new therapeutic agents will be discovered for this rare condition.

CONFLICT of INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Tazi A. Adult pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. Eur Respir J 2006; 27: 1272-85.

- Suri HS, Yi ES, Nowakowski GS, Vassallo R. Pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012; 7: 16.

- Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, Jaffe ES, Weiss LM, Arico M, et al. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. The WHO Committee on Histiocytic/Reticulum Cell Proliferations. Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol 1997; 29: 157-66.

- Howarth DM, Gilchrist GS, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Edmonson JH, Schomberg PJ. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: diagnosis, natural history, management, and outcome. Cancer 1999; 85: 2278-90.

- Landi C, Bargagli E, Magi B, Prasse A, Muller-Quernheim J, Bini L, et al. Proteome analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage in pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Clin Bioinforma 2011; 1: 31.

- Tazi A, Soler P, Hance AJ. Adult pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. Thorax 2000; 55: 405-16.

- Caminati A, Harari S. Smoking-related interstitial pneumonias and pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006; 3: 299-306.

- Harari S, Comel A. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2001; 18: 253-62.

- Basset F, Corrin B, Spencer H. Pulmonary histiocytosis X. Am Rev Respir Dis 1978; 118: 811-20.

- Braier J, Latella A, Balancini B, Casta?os C, Rosso D, Chantada G, et al. Outcome in children with pulmonary Langerhans cell Histiocytosis. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2004; 43: 765-769.

- Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Schroeder DR, Decker PA, Limper AH. Clinical outcomes of pulmonary Langerhans'-cell histiocytosis in adults. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 484-90.

- Travis WD, Borok Z, Roum JH, Zhang J, Feuerstein I, Ferrans VJ, et al. Pulmonary Langerhans cell granulomatosis (histiocytosis X). A clinicopathologicstudy of 48 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1993; 17: 971-86.

- Sch?nfeld N, Frank W, Wenig S, Uhrmeister P, Allica E, Preussler H, et al. Clinical and radiologic features, lung function and therapeutic results in pulmonary histiocytosis X. Respiration 1993; 60: 38-44.

- Lacronique J, Roth C, Battesti JP, Basset F, Chretien J. Chest radiological features of pulmonary histiocytosis X: a report based on 50 adult cases. Thorax 1982; 37: 104-9.

- Seely JM, Salahudeen S Sr, Cadaval-Goncalves AT, Jamieson DH, Dennie CJ, Matzinger FR, et al. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a comparative study of computed tomography in children and adults. J Thorac Imaging 2012; 27: 65-70.

- Brauner MW, Grenier P, Mouelhi MM, Mompoint D, Lenoir S. Pulmonary histiocytosis X: evaluation with high-resolution CT. Radiology 1989; 172: 255-8.

- Bonelli FS, Hartman TE, Swensen SJ, Sherrick A. Accuracy of high resolution CT in diagnosing lung diseases.? Am J Roentgenol 1998; 170: 1507-12.

- Hartman TE, Tazelaar HD, Swensen SJ, M?ller NL. Cigarette smoking: CT and pathologic findings of associated pulmonary diseases. Radiographics 1997; 17: 377-90.

- Abbritti M, Mazzei MA, Bargagli E, et al. Utility of spiral CAT scan in the follow-up of patients with pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81: 1907-12.

- Tazi A, Marc K, Dominique S, de Bazelaire C, Crestani B, Chinet T, et al. Serial computed tomography and lung function testing in pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 905-12.

- Juvet SC, Hwang D, Downey GP. Rare lung diseases III: pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. Can Respir J 2010; 17: e55-62.

- Housini I, Tomashefski JF Jr, Cohen A, Crass J, Kleinerman J. Transbronchial biopsy in patients with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma. Comparison with findings on open lung biopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1994; 118: 523-30.

- Smetana K Jr, Mericka O, Saeland S, Homolka J, Brabec J, Gabius HJ. Diagnostic relevance of Langerin detection in cells from bronchoalveolar lavage of patients with pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Virchows Arch 2004; 444: 171-4.

- Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Colby TV, Hartman T, Limper AH. Pulmonary Langerhans'-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1969-78.

- Caponetti GC, Miranda RN, Althof PA, Dobesh RC, Sanger WG, Medeiros LJ, et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular cytogenetic evaluation of potential targets for tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hum Pathol 2012; 43: 2223-8.

Yaz??ma Adresi (Address for Correspondence):

Dr. Ersin G?NAY,

Afyon Kocatepe ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi,

G???s Hastal?klar? Anabilim Dal?, 03200

AFYONKARAH?SAR - TURKEY

e-mail: ersingunay@gmail.com