Kad?nlarda ?nemli bir sa?l?k tehdidi olarak biomass maruziyeti

Aylin BABALIK1, Nadi BAKIRCI2, Mah?uk TAYLAN1, Leyla BOSTAN1, ?ule KIZILTA?1, Yelda BA?BU?1,

Haluk C. ?ALI?IR1

1 SB S?reyyapa?a G???s Hastal?klar? ve G???s Cerrahisi E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi,

G???s Hastal?klar? Klini?i, ?stanbul,

2 Ac?badem ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi, Halk Sa?l??? Anabilim Dal?, ?stanbul.

?ZET

Kad?nlarda ?nemli bir sa?l?k tehdidi olarak biomass maruziyeti

Giri?: ?zellikle kad?nlarda, sa?l??a zararl? partik?lleriyle birlikte biomass, akci?er hastal?klar?na neden olmaktad?r. Bu ?al??ma, kad?nlarda akci?er hastal???na sebep olan biomass maruziyetini ara?t?rmak i?in planlanm??t?r.

Materyal ve Metod: Eyl?l 2008-Mart 2009 tarihleri aras?nda S?reyyapa?a G???s Hastal?klar? ve G???s Cerrahisi E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesinde yat?r?larak tedavi edilen kronik obstr?ktif akci?er hastal??? (KOAH), ast?m, bron?ektazi, t?berk?loz veya interstisyel akci?er hastal??? olan toplam 100 kad?n (ortalama ya? 55.13 ? 17.65 y?l) hasta ?al??maya dahil edildi. Biomass maruziyeti konusunda veri toplanmas?, hastanede meslek, e?itim seviyesi, do?um yeri, ?s?tma ve pi?irme s?ras?nda biomass duman?na maruz kalma (tezek, odun, k?m?r, kuru bitkiler) ve maruziyet y?l? de?erlendirildi.

Bulgular: KOAH (%22), akci?er kanseri (%12), bron?it (%8), t?berk?loz (%26) ve interstisyel akci?er hastal??? (%17) olan kad?nlar ?al??maya dahil edildi. En s?k saptanan meslek ev han?ml??? idi (%86). Sigaray? aktif kullananlar?n, b?rakm?? olanlar?n ve hi? kullanmam?? olanlar?n oranlar? s?ras?yla %6, %22 ve %72 idi. Hastalar?n %67'si k?yde, %9'u il?ede do?mu?tu. B?lge da??l?m?na g?re, en s?k b?lge %29 oran?yla ?? Anadolu B?lgesi idi. Biomassa maruziyet en s?k, odun (%92), tezek (%30), k?m?r (%23) ve kuru bitkiler (%23) ile olmaktad?r. Ortalama maruziyet y?l? odun i?in 52.6 (17.6) y?l, tezek i?in 40.8 (17.9) y?l, kuru bitkiler i?in 48.1 (20.8) y?l ve k?m?r i?in 38.5 (21.4) y?ld?. En s?k biomass maruziyeti, %97 oran?yla k?yde, %79 oran?yla ?ehirde ve %89 oran?yla t?m ?lkede ?eklindeydi.

Sonu?: Bizim bulgular?m?z, kad?nlarda biomass maruziyetinin ?nemini g?stermektedir. Ayn? zamanda kad?nlar ve ?ocuklar i?in maruziyet seviyesini ?l?en detayl? analitik epidemiyolojik ?al??malara gerek oldu?unu g?sterir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Biomass maruziyeti, solunumsal hastal?k, kad?n, T?rkiye.

SUMMARY

Biomass smoke exposure as a serious health hazard for women

Aylin BABALIK1, Nadi BAKIRCI2, Mah?uk TAYLAN1, Leyla BOSTAN1, ?ule KIZILTA?1, Yelda BA?BU?1,

Haluk C. ?ALI?IR1

1 Clinic of Chest Diseases, Sureyyapasa Chest Diseases and Chest Surgery Training and Research Hospital,

Istanbul, Turkey,

2 Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Acibadem University, Istanbul, Turkey.

Introduction: Lung diseases caused by biomass exposure cause a significant health hazard particularly amongst women. The present study was designed to investigate biomass exposure in women suffering from lung disease.

Materials and Methods: A total of 100 women [mean (SD) age: 55.13 (17.65) years] hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis or interstitial lung disease were included in this study conducted between September 2008-March 2009 in three chest disease clinics at Sureyyapasa Chest Diseases and Chest Surgery Training and Research Hospital. Data collection on biomass exposure was based on application of hospital-based survey questionnaire including items on occupation, level of education, place of birth (location, region), exposure to biomass fuel fumes for heating and cooking purposes (animal dung, wood, charcoal, dried plant) and years of exposure with animal dung, wood, charcoal, dried plant.

Results: COPD in 22% patients, lung carcinoma in 12%, bronchitis in 8%, tuberculosis in 26%, and interstitial lung disease in 17% were the diagnosis for hospitalization. The most identified occupation was housewifery 86%. Active, former and non-smokers composed 6%, 22% and 72% of the population. Birth place was village in 67% patients while districts in 9%. According to regional distribution, the most common place of birth was Central Anatolia region in (29%). Exposure to biomass fuels was identified in all of patients including wood (92%), animal dung (30%), charcoal (23%), and dry plant (23%). Mean (SD) years of exposure was identified to be 52.6 (17.9) years for wood, 40.8 (17.9) years for animal dung, 48.1 (20.8) years for dry plant and 38.5 (21.4) years for charcoal. The most common type of biomass exposure was wood in village (97%), city (79%) and county (89%).

Conclusion: Findings indicating impact of biomass exposure in women seem to emphasize the need for analytic epidemiologic studies assessment measuring biomass exposure levels-particularly for women and young children.

Key Words: Biomass exposure, respiratory disease, women, Turkey.

Tuberk Toraks 2013; 61(2): 115-121 • doi: 10.5578/tt.4173

Geli? Tarihi/Received: 19/11/2011 - Kabul Edili? Tarihi/Accepted: 11/03/2013

Introduction

Indoor air pollution (IAP) is a major environmental and public health hazard for many of the world's poorest most vulnerable people. There has been an increasing scientific interest in indoor pollution since the second half of 1980 (1). IAP resulting from combustion of biomass fuels has now been recognised as a relevant risk factor for respiratory disorders especially in developing countries in relation to the shift from use of biofuel to petroleum products (kerosene, LPG) and electricity in developed countries (2).

Biomass fuel, or biofuel, refers to any plant or animal based material deliberately burned by humans as their primary source of domestic energy for cooking, home heating and lightening. While the wood is the most common biofuel, use of animal dung and crop residues is also widespread (2). Typically burnt in open fires or poorly functioning stoves, the use of these fuels leads to very high levels of IAP. Smoke exposure affects mainly women and also young children accompanying their mothers during cooking and other household activities (2).

Around 50% of the world's population uses biomass fuels ranging from near zero in industrialized countries to more than 80% in countries like China, India and sub- Saharan Africa. In Latin America, approximately 50-75% of households were reported to use biomass fuels for cooking, especially in rural areas (1). In Turkey, use of biomass fuels was documented to be 30% in urbanized areas; 30% in rural areas and 90% in Central Anatolia, East Anatolia and Southeastern Anatolia regions (3).

Biomass smoke contains thousands of substances, many of which have a significant potential to damage human health. The most damaging substances are carbon monoxide, nitrous dioxides, sulphur oxides (more with coal), formaldehyde and polycyclic organic matter which includes carcinogens such as benzo(a)pyrene (1,2).

There is now consistent evidence that biomass smoke exposure increases respiratory and non-respiratory diseases. A significant relation of smoke exposures to the risk of childhood acute respiratory infections, pneumonia in particular and respiratory diseases seen in women including chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, lung cancer and lung fibrosis was demonstrated. Besides, evidence of an increased risk of tuberculosis was also shown by a number of studies (1,2).

The present study was designed to investigate the effects of biomass exposure in hospitalized women suffering from lung disease.

MATERIALS and METHODS

A total of 100 women [mean (SD) age: 55.13 (17.65) years] hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis or interstitial lung disease were included in this study conducted between September 2008-March 2009 in three chest disease clinics at the Sureyyapasa Chest Diseases and Chest Surgery Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Being ≥ 18 years of age and to be hospitalized for a respiratory disease including asthma, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis and interstitial lung disease were the inclusion criteria. Patients lacking a definite clinical diagnosis or cooperation to answer questionnaire were excluded from the study.

Data collection on biomass exposure was based on application of hospital-based survey questionnaire to the study sample selected through random sampling. Questionnaire included items on occupation, level of education, place of birth (location, region), exposure to biomass fuel fumes for heating and cooking purposes (animal dung, wood, charcoal, dried plant) and years of exposure with animal dung, wood, charcoal, dried plant. Besides use of flueless systems such as floor furnace, barbecue, fireplace or bottled gas for heating was considered to be risky exposure and years of exposure was also recorded for the heating methods.

Data on symptoms, respiratory function tests, findings of spirometry, physical examination, high resolution of computerized tomography, chest X-ray, bacteriological investigation (sputum smear and culture results) were collected from medical records.

COPD diagnosis was made via spirometry and clinical assessment and patients who had spirometric measurement FEV1/FVC < 0.70 and characteristic symptoms of COPD such as chronic and progressive dyspnea, cough and sputum production were considered to have COPD according to GOLD guidelines (4).

Patients who had symptoms of recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing at night or early morning and who were under asthma treatment were considered to have asthma in accordance with GINA guidelines (5).

Diagnosis of tuberculosis was based on smear or culture positivity of bacteriological sputum or histopathological confirmation. Diagnosis of interstitial lung disease and bronchiectasis was performed radiologically via high resolution of computerized tomography.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used. Continuous variables will be summarized using mean and standard deviation (for normally distributed variables) and median and quartiles (for non-normally distributed variables). Categorical variables will be summarized with percent in each category.

Results

Mean (SD) age of the study population composed of 100 women was 55.13 (17.65) years.

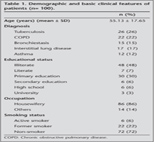

COPD in 22 (22%) patients, lung carcinoma in 12 (12%) patients, bronchitis in 8 (8%) patients, tuberculosis in 26 (26%) patients, and interstitial lung disease in 17 (17%) patients were the diagnosis for hospitalization. Of 100 patients 48 (48%) were illiterate, while 3 (33.3%) were university graduates. The most commonly identified occupation was housewifery (86%). Active, former and non-smokers composed 6%, 22% and 72% of the population, respectively and 66.7% of non-smokers identified evidence of passive smoking due to presence of other smokers at home (Table 1).

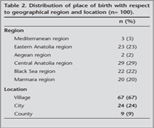

Birth place location was village in 67% patients while districts in 9%. According to regional distribution, place of birth was Central Anatolia region in 29 (29%), Eastern Anatolia region in 23 (23%), Black Sea region in 22 (22%), Marmara region in 20 (20%), Mediterranean region in 3 (3%) and Aegean region in 2 (2%) (Table 2).

Migration was evident in 12 (12%) patients in the first decade of their lives while 37 (37%) patients identified that they migrated in the second decade and 60 (60%) patients in the third decade of their lives.

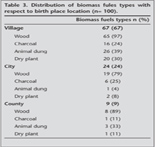

The most common type of biomass exposure was wood in village (97%), city (79%) and county (89%) (Table 3).

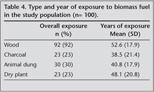

Exposure to biomass fuels was identified in all of patients including wood (92%), animal dung (30%), charcoal (23%), and dry plant (23%). Mean (SD) years of exposure was identified to be 52.6 (17.9) years for wood, 40.8 (17.9) years for animal dung, 48.1 (20.8) years for dry plant and 38.5 (21.4) years for charcoal (Table 4).

Discussion

COPD, asthma, lung fibrosis, interstitial lung diseases, pulmonary tuberculosis and lung cancer are considered among the respiratory diseases associated with exposure of IAP. Women and children seem to be at greater risk of adverse health effects resulting from the IAP since they spend more time indoors compared to rest of the population (1).

Accordingly in our study population composed primarily of housewives (86%) who were spending majority of their time indoors with household activities, the significant exposure to biomass fumes from the heating and cooking was evident. Indeed, all of the women included this study was identified to have biomass fuels exposure in the past, especially early years of their lives with almost more than 40 years of average exposure to animal dung, dry plant and charcoal.

People from lower socioeconomic status have been considered to be more susceptible to tuberculosis which is a significant socioeconomic public health issue (6). In this line, indicating higher use of biomass fuels in rural areas of Turkey including people from lower socioeconomic level, Central Anatolia (29%) and Eastern Anatolia (23%) were the most commonly identified geographical regions of place of birth and to be born in a village (67%) predominated in our population. Besides, in correlation to their low socioeconomic level, half of our patients were identified to be illiterate.

While wood has been considered as the most commonly used biofuel, use of animal dung and crop residues was also documented to be widespread (7). Accordingly wood usage was very common (93%) in our population.

The evaluation of the medical records showed that out of 100 female patients, tuberculosis was evident in 26%, COPD in 22%, bronchiectasis in 15%, interstitial diseases in 17%, and asthma in %12.

IAP has been considered a risk factor for COPD by the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (4). Albeit not consistent, the association between IAP exposure and increased risk of chronic bronchitis with possible progression to COPD, emphysema and cor pulmonale was reported in majority of studies. Accordingly, the association between exposure to biomass smoke and chronic bronchitis or COPD was documented in some cross-sectional, case control and cohort studies. Exposure was usually estimated via questionnaires based on hours by the wood stove, or hours multiplied by years of exposure. The evidence for chronic bronchitis has generally been defined by questionnaire symptoms. Spirometrical evaluation was done. Additionally, women exposed to biomass fumes were reported to be more likely to suffer from chronic bronchitis and COPD compared with urban women even though the prevalence of smoking was higher among the latter group (8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15).

In Turkey and Iran, women exposed to biomass for cooking/heating showed significantly higher prevalence of chronic bronchitis and COPD while recent studies showed contribution of wood smoke and poverty to reduced lung function as an important risk factor for development of COPD among non-smoking women (16,17,18).

First large epidemiological study conducted in Turkey showed that biomass exposure, as a sole reason for COPD, was significantly common among female patients living in rural areas (54.5%) (19). In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 25 studies concerning respiratory diseases associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children, the overall pooled ORs indicated significant associations with chronic bronchitis in women (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.88 to 3.38) and COPD in women (OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.47 to 3.93) (20).

There are still relatively few published studies from developing countries about the relation between asthma and IAP while exposure is not measured and confounding is not dealt with in some of these studies. Although evidence from developing countries suggests that IAP may increase risk of developing asthma for children, a number of studies reported no effect for children (8,21,22,23,24,25).

Evidence in adults comes from in rural China which reported adjusted OR for wheezing and asthma for the group with occupational exposure to wood smoke to be 1.36 (1.14-1.61) and 1.27 (1.02-1.58), respectively (20,24). In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 25 studies concerning respiratory diseases associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children, no significant association with asthma in children or women was noted (20).

A few studies have found an increased risk of tuberculosis from exposure biomass fuels, although none of them measured the level of exposure specifically and confounding not fully accounted for in one (26,27,28). In these studies, adjusted OR for socio-economic factors OR were 2.58 (1.98-3.37), 2.4 (1.04-5.6) (26,27,28). Association between use of biofuel and tuberculosis was found similar with adjustment only for age (27). An increase in risk of tuberculosis may result from reduced resistance to infection, as exposure to smoke interferes with mucociliary defenses and decreases antibacterial properties of lung macrophages (29). Biomass smoke exposure may be an additional factor in the well-established relationship between poverty and tuberculosis and may be explained by factors including malnutrition, overcrowding and limited access to health care.

There is some evidence also that wood smoke exposure may be associated with interstitial lung disease (inflammation of the lung structure leading to fibrosis) in developed countries (30,31,32). In a small case control study, patients with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis were determined to be more likely to live in a house heated by a wood fire (33). Several studies have described lung fibrosis which resembles pneumoconiosis including cases with progressive massive fibrosis among subjects exposed to wood smoke. Exposure to inorganic or organic dusts may coexist in these patients. Non-occupational silicosis has also been reported in developing countries, and attributed to sand storms, but these subjects have often also exposed to biomass smoke (34,35,36).

The existing studies on the relationship between biomass usage and respiratory diseases in developing countries, provide important evidence of associations with a range of serious and common health problems but suffer from a number of methodological limitations, namely:

a. The lack of detailed and systematic pollution exposure determination,

b. The fact that all studies to date have been observational and,

c. That many have dealt inadequately with confounding (1).

In conclusion, poverty is one of the main barriers to the adoption of cleaner fuels and slow pace of development in many countries implies that biofuels will continue to be used by the poor for many decades. The available data indicate the significant impact of biomass fuels usage on the respiratory health worldwide and that protective public health measures should be implemented (1). Our findings indicating significant impact of biomass exposure in women seem to emphasize the need for the detailed analytic epidemiologic studies concerning assessment biomass exposure to be able develop practical, robust and valid methods for measuring the exposure levels and patterns-particularly for women and young children.

CONFLICT of INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Viegi G, Simoni M, Scognamiglio A, Baldacci S, Pistelli F, Carrozzi L, et al. Indoor air pollution and airway disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004; 8: 1401-15.

- World Health Organization Protection of the Human Environment. The health effects of indoor air pollution exposure in developing countries. Geneva, 2002.

- Baris YI, Hoskins JA, Seyfikli Z, Demir A. Biomass lung: primitive biomass combustion and lung disease indoor and built environment 2002; 11: 351-8.

- Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (up dated 2010).

- Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, Drazen JM, FitzGerald M, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J 2008; 31: 143-78.

- Muniyandi M, Ramachandran R, Gopi PG, Chandrasekaran V, Subramani R, Sadacharam K, et al. The prevalence of tuberculosis in different economic strata: a community survey from South India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007; 11: 1042-5.

- De Koning HW, Smith KR, Last JM. Biomass fuel combustion and health. Bull WHO 1985; 63: 11-26.

- Ellegard A. Cooking fuel smoke and respiratory symptoms among women in low-income areas in Maputo. Environ Health Perspect 1996; 104: 980-5.

- Albalak R, Frisancho AR, Keeler GJ. Domestic biomass fuel combustion and chronic bronchitis in two rural Bolivian villages. Thorax 1999; 54: 1004-8.

- Menezes AM, Victora CG, Rigatto M. Prevalence and risk factors for chronic bronchitis in Pelotas, RS, Brazil: a population based study. Thorax 1994; 49: 1217-21.

- Qureshi K. Domestic smoke pollution and prevalence of chronic bronchitis/asthma in a rural area of Kashmir. Indain J Chest Dis Allied Sci 1994; 36: 61-72.

- Regalado J, Perez-Padilla R, Sansores R, Vedal S, Brauer M, Pare P. The effect of biomass burning on respiratory symptoms and lung function in rural Mexican women. Am J Respir Crit Car Med 1996; 153: A701.

- Dennis RJ, Maldonado D, Norman S, Baena E, Casta?o H, Martinez G, et al. Wood smoke exposure and risk for obstructive airways disease among women. Chest 1996; 109(3 Suppl): 55S-56S. No abstract available.

- Perez-Padilla JR, Moran O, Salazar M, Vazquez F. Chronic bronchitis associated with domestic inhalation of wood smoke in Mexico: clinical, functional and pathological description. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993; 147: A631.

- Kiraz K, Kart L, Demir R, Oymak S, Gulmez I, Unalacak M, et al. Chronic pulmonary disease in rural women exposed to biomass fumes. Clin Invest Med 2003; 26: 243-8.

- Golshan M, Faghihi M, Marandi MM. Indoor women jobs and pulmonary risks in rural areas of Isfahan, Iran, 2000. Respir Med 2002; 96: 382-8.

- Fullerton DG, Suseno A, Semple S, Kalambo F, Malamba R, White S, et al. Wood smoke exposure, poverty and impaired lung function in Malawian adults. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011; 15: 391-8.

- Chan-Yeung M, A?t-Khaled N, White N, Ip MS, Tan WC. The burden and impact of COPD in Asia and Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004; 8: 2-14.

- Prevalence of COPD: first epidemiological study of a large region in Turkey Top of Form. Eur J Int Med 2008; 19: 499-504.

- Po JY, Fitz Gerald JM, Carlsten C. Respiratory disease associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2011; 66: 232-9.

- Melsom T, Brinch L, Hessen JO, Schei MA, Kolstrup N, Jacobsen BK, et al. Asthma and indoor environment in Nepal. Thorax 2001; 56: 477-81.

- Schei MA, Hessen JO, McCracken J, Lopez V, Bruce NG, Smith KR. Asthma and indoor air pollution among indigenous children in Guatemala. Proc Indoor Air 2002, Monterey, CA (1st-7th July 2002).

- Gharaibeh NS. Effects of indoor air pollution on lung function of primary school children in Jordan. Ann Trop Paed 1996; 16: 97-102.

- Xu X, Niu T, Christiani DC, Weiss ST, Chen C, Zhou Y, et al. Occupational and environmental risk factors for asthma in rural communities in China. Int J Occup Environ Health 1996; 2: 172-6.

- Noorhassim I, Rampal KG, Hashim JH. The relationship between prevalence of asthma and environmental factors in rural households. Med J Malaysia 1995; 50: 263-7.

- Mishra VK, Retherford RD, Smith KR. Biomass cooking fuels and prevalence of Tuberculosis in India. Int J Infect Dis 1999; 3: 119-29.

- Gupta BN, Mathur N. A study of the household environmental risk factors pertaining to respiratory disease. Energy Environ Rev 1997; 13: 61-7.

- Perez- Padilla J, Perez-Guzman C, Baez-Saldana R, Torres-Cruz A. Cooking with biomass stoves and tuberculosis: a case-control study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2001; 5: 1-7.

- Houtmeyers E, Gosselink R, Gayan-Ramirez G, Decramer M. Regulation of mucociliary clearance in health and disease. Eur Respir J 1999; 13: 1177-88.

- Restrepo J, Reyes P, De Ochoa P, Patino E. Neumoconiosis por inhalacion del humo de le?a. Acta Medica Colombiana 1983; 8: 191-204.

- Grobbelaar JP, Bateman ED. Hut lung: a domestically acquired pneumoconiosis of mixed etiology in rural women. Thorax 1991; 46: 334-40.

- Dhar SN, Pathania AGS. Bronchitis due to biomass fuel burning in north India: "Gujjar Lung", an extreme effect. Semin Respir Med 1991; 12: 69-74.

- Scott J, Johnston I, Britton J. What causes cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis? A case-control study of environmental exposure to dust. Br Med J 1990; 301: 1015-7.

- Norboo T, Angchuk PT, Yahya M. Silicosis in an Himalayan village population: role of environmental dust. Thorax 1991; 46: 341-3.

- Norboo T, Yahya M, Bruce N, Heady A, Ball K. Domestic pollution and respiratory illness in a Himalayan village. Int J Epidemiol 1991; 20: 749-57.

- Saiyed HN, Sharma YK, Sadhu HG, Norboo T, Patel PD, Patel TS, et al. Nonoccupational pneumoconiosis at high altitude villages in central Ladakh. Br J Ind Med 1991; 48: 825-9.

Yaz??ma Adresi (Address for Correspondence):

Dr. Aylin BABALIK,

SB S?reyyapa?a G???s Hastal?klar? ve

G???s Cerrahisi E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi,

G???s Hastal?klar? Klini?i,

?STANBUL - TURKEY

e-mail: aylinbabalik@gmail.com