Kronik

obstr?ktif akci?er hastal???n?n g?nl?k ya?am aktivitelerine etkilerini

ara?t?rmaya y?nelik kesitsel g?zlem ?al??mas?: KOAH'la Ya?am ?al??mas?

Mehmet

POLATLI1, Cahit B?LG?N2, Beng? ?AYLAN3, ?eyma

BA?LILAR3, Evren TOPRAK4,

Hasan ERGEN5, Nur Dilek BAKAN6, Levent KART7,

Zennur KILI?8, Azize ?ST?NEL9,

Ahmet ?ENG?N10,

Yelda VAROL11, Adem YILMAZ12, ?a?atay ATAOL13,

Didem BULGUR14,

Serap BOZDO?AN14, ?lknur TUNABOYU15,

Zehra G?lcihan ?ZKAN6, Ekrem UYSAL16,

Sevtap G?LG?STEREN17,

Ne?e AKIN18, Yavuz Selim ?NTEPE19, Mustafa IRMAK20,

Erhan TURGUT21,

Olgun KESK?N22, Hilal BEKTA? UYSAL23,

Nevin SOFUO?LU24, Mehmet YILMAZ25

(KOAH'la Ya?am ?al??ma

Grubu; ?al??maya al?nan hasta say?lar?na g?re isimler s?ralanm??t?r)

1 Adnan Menderes ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi Hastanesi, Ayd?n,

2 Hendek Devlet Hastanesi, Sakarya,

3 ?mraniye E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi, ?stanbul,

4 Burdur Devlet Hastanesi, Burdur,

5 Giresun G???s Hastal?klar? Hastanesi, Giresun,

6 Yedikule G???s Hastal?klar? Hastanesi, ?stanbul,

7 Vak?f ?niversitesi Hastanesi, ?stanbul,

8 Gebze Fatih Devlet Hastanesi, Kocaeli,

9 Kayseri E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi, Kayseri,

10 Etlik ?htisas E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi, ?entepe Semt Poliklini?i, Ankara,

11 Torbal? Devlet Hastanesi, ?zmir

12 Adana ?ukurova Devlet Hastanesi, Adana,

13 Antalya E?itim ve Ara?t?rma Hastanesi, Antalya,

14 Gaziantep Av. Cengiz G?k?ek Devlet Hastanesi, Gaziantep,

15 Ayd?n Atat?rk Devlet Hastanesi, Ayd?n,

16 Bursa T?rkan Akyol G???s Hastal?klar? Hastanesi, Bursa,

17 Ilg?n Vefa DevletHastanesi, Konya,

18 Bart?n Devlet Hastanesi, Bart?n,

19 Yozgat Devlet Hastanesi, Yozgat,

20 Adana G???sHastal?klar? Hastanesi, Adana,

21 Isparta G?lkent Devlet Hastanesi, Isparta,

22 Anamur Devlet Hastanesi, Mersin,

23 Ilgaz Devlet Hastanesi, ?ank?r?,

24 ?zel 8 Eyl?l Hastanesi, Manisa,

25 Safranbolu Devlet Hastanesi, Karab?k.

?ZET

Kronik obstr?ktif akci?er hastal???n?n g?nl?k ya?am aktivitelerine etkilerini ara?t?rmaya y?nelik kesitsel g?zlem ?al??mas?: KOAH'la Ya?am ?al??mas?

Giri?: ?al??ma kronik obstr?ktif akci?er hastal??? (KOAH)'n?n hastalar?n g?nl?k ya?am aktivitelerine etkilerinin ve hastalar?n g?nl?k ya?amlar?n? s?rd?rme bi?imleri ve gereksinimlerinin belirlenmesi amac?yla tasarland?.

Hastalar ve Metod: Bu ulusal, ?ok merkezli, kesitsel g?zlem ?al??mas?na, 41 merkezden, eski ve yeni tan?l? toplam 497 stabil KOAH hastas? [ortalama ya? (standart sapma; SS): 63.3 (9.3) y?l; %59.0'u < 65 ya?, %89.9'u erkek] dahil edildi. Sosyodemografi ve KOAH ile ilgili veriler kay?t viziti ve bu viziti takiben bir ay i?inde hastalarla ger?ekle?tirilen telefon g?r??mesi yoluyla elde edildi.

Bulgular: Ortalama (SS) KOAH s?resi t?m hastalar i?in 7.3 (6.5) y?l, semptomlar?n ba?lang?c?ndan sonra bir y?l ve daha ge? bir zamanda tan? alan hastalar i?in 5.4 (4.6) y?ld?. Dispne (%83.1) en s?k g?r?len semptom, merdiven ??kma (%66.6) en zorlan?lan aktiviteydi. Hastalar?n ?o?unlu?u KOAH'?n kronik bir hastal?k oldu?unun (%63.4), s?rekli tedavi gerektirdi?inin (%79.7), temel nedenin sigara i?me oldu?unun (%63.5) bilincindeydi. T?rkiye'deki 45-65 ya? aral???nda olan KOAH hastalar?n?n oran? %59 olarak tespit edildi. Hastalar?n %84'?n?n en az ilkokul mezunu oldu?u g?zlemlenmi?tir. ?al??ma sonu?lar?na g?re hastalar?n ortalama iki ki?iye bakmakla y?k?ml? olduklar? ve %91'inin evden d??ar? ??kabilirken, ??te ikisinden fazlas?n?n bakkala ve pazara rahat gidebildikleri tespit edildi. Gerek e?itim durumu, gerekse ya? gruplar? aras?nda cihaz?n d?zenli kullan?m?n?n da??l?m? a??s?ndan anlaml? bir farkl?l?k bulunamad?. Hastalar?n KOAH tedavisinden beklentilerinde nefes alabilmek (%24.1), y?r?mek (%17.1) ve merdiven ??kmak (%11.7) ilk ?? s?rada yer al?rken, nefes darl??? (%43.3) ?ncelikli tedavi gereksinimi olarak ifade edildi.

Sonu?: Bu ?al??mada KOAH'?n ya?l? hastalarda g?r?ld??? izlenimine ters olarak, gen? hasta oran?n?n d???n?lenden daha y?ksek oldu?u, hastalar?n ?nemli bir b?l?m?n?n ev d???na ??kma zorunlulu?u oldu?u ve KOAH hastalar?nda cihazlar?n? d?zenli olarak kullanma durumunun e?itim ve ya?tan ba??ms?z oldu?u g?r?lm??t?r. Bulgular?m?z genel kan?n?n aksine, KOAH'?n sadece ya?l? hastalara ?zg? bir hastal?k olmay?p KOAH hastalar?n?n hayat?n i?inde ve aktif olduklar?na ve vakitlerinin ?o?unu evde ve yatakta ge?irmediklerine i?aret etmektedir. Dolay?s?yla, tedavilerinde her zaman yanlar?nda ta??yabilecekleri ve kolay kullan?lan bir cihaz?n, hayat?n i?inde ya?amlar?n? s?rd?ren bu hastalar?n g?nl?k ya?amlar?n? iyile?tirmedeki ?nemi ortaya ??kmaktad?r.

Anahtar Kelimeler: KOAH, semptomlar, g?nl?k ya?am aktiviteleri, hasta profili, terap?tik beklentiler.

SUMMARY

A cross sectional observational study on the influence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on activities of daily living: the COPD-Life study

Mehmet

POLATLI1, Cahit B?LG?N2, Beng? ?AYLAN3, ?eyma

BA?LILAR3, Evren TOPRAK4,

Hasan ERGEN5, Nur Dilek BAKAN6, Levent KART7,

Zennur KILI?8, Azize ?ST?NEL9,

Ahmet ?ENG?N10,

Yelda VAROL11, Adem YILMAZ12, ?a?atay ATAOL13,

Didem BULGUR14,

Serap BOZDO?AN14, ?lknur TUNABOYU15,

Zehra G?lcihan ?ZKAN6, Ekrem UYSAL16,

Sevtap G?LG?STEREN17,

Ne?e AKIN18, Yavuz SEL?M19, Mustafa IRMAK20,

Erhan TURGUT21,

Olgun KESK?N22, Hilal BEKTA? UYSAL23,

Nevin SOFUO?LU24, Mehmet YILMAZ25

(The COPD-Life Study

Group; sites are listed in order of number of patients included)

1 Faculty of Medicine Hospital, Adnan Menderes University, Aydin, Turkey,

2 Hendek State Hospital, Sakarya, Turkey,

3 Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey,

4 Burdur State Hospital, Burdur, Turkey,

5 Giresun Chest Diseases Hospital, Giresun, Turkey,

6 Yedikule Chest Diseases Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey,

7 Vak?f University Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey,

8 Gebze Fatih State Hospital, Kocaeli, Turkey,

9 Kayseri Training and Research Hospital, Kayseri, Turkey,

10 Etlik Speciality Training and Research Hospital, Sentepe Neighborhood Clinic, Ankara, Turkey,

11 Torbali State Hospital, Izmir, Turkey,

12 Adana Cukurova State Hospital, Adana, Turkey,

13 Antalya Training and Research Hospital, Antalya,

14 Gaziantep Av. Cengiz Gokcek State Hospital, Gaziantep, Turkey,

15 Aydin Ataturk State Hospital, Aydin, Turkey,

16 Bursa Turkan Akyol Chest Diseases Hospital, Bursa, Turkey,

17 Ilgin Vefa State Hospital, Konya, Turkey,

18 Bartin State Hospital, Bartin, Turkey,

19 Intepe Yozgat State Hospital, Yozgat, Turkey,

20 Adana Chest Diseases Hospital, Adana, Turkey,

21 Isparta Gulkent State Hospital, Isparta, Turkey,

22 Anamur State Hospital, Mersin, Turkey,

23 Ilgaz State Hospital, Cankiri, Turkey,

24 8 Eylul Private Hospital, Manisa, Turkey,

25 Safranbolu State Hospital, Karabuk, Turkey.

Introduction: This study was designed to identify the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on activities of daily living, life styles and needs in patients.

Patients and Methods: Participants of this national, multi-centered, cross-sectional observational study included 497 stable COPD patients from 41 centers. The mean age (standard deviation; SD) was 63.3 (9.3) years with 59.0% of the patients under the age of 65, and 89.9% of the participants were male. Sociodemographic and COPD-related data were gathered at enrollment and during the 1-month telephone follow-up.

Results: The mean (SD) COPD duration was 7.3 (6.5) years in the overall population while 5.4 (4.6) years for patients who recieved COPD diagnosis at least one year after the onset of symptoms. Dyspnea was the most common (83.1%) symptom and walking up stairs (66.6%) was the most difficult activity to be performed. Majority of the patients were aware of COPD as a chronic disease (63.4%), requiring ongoing treatment (79.7%), mainly caused by smoking (63.5%). 59% of the patients were under the age of 65 years-old. In 84% of patients, graduation from at least a primary school was identified. Results revealed an average number of two dependants that were obliged to look after per patient, ability to go on an outing in 91% of the patients, and going grocery shopping with ease in more than two-thirds of the study population. There was no significant difference in regular use of medication device across different educational or age groups. The top three COPD treatment expectations of the patients were being able to breathe (24.1%), walking (17.1%), and walking up stairs (11.7%), while shortness of breath (43.3%) was the first priority treatment need.

Conclusion: In contrast to the common view that COPD prevalance is higher in old age population, this study showed that the rate of the disease is higher among younger patients than expected; indispensability of out of the house activities in majority of patients; and use of regular medication device to be independent of educational level and the age of COPD patients. Our findings indicate that the likelihood of COPD patient population to be composed of younger and active individuals who do not spend majority of their time at home/in bed as opposed to popular belief. Therefore, availability of a portable and easy to use device for medication seems to be important to enhance daily living.

Key Words: COPD, symptoms, activities of daily living, patient profile, therapeutic expectations.

Geli? Tarihi/Received: 19/12/2011 - Kabul Edili? Tarihi/Accepted: 23/02/2012

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the most common chronic diseases in the world with 600 million patients worldwide, and based on World Health Organization's (WHO) data, it is expected to be the third most common cause of death by 2020 (1,2). In comparison to other chronic diseases, COPD is an important burdensome disease due to characteristics of symptoms and related functional limitations (3,4). Compared to the current treatment methods, smoking cessation has been considered as the most important intervention to limit the progression of the disease which brings significant personal, social and economic burden (1,5).

The principal goals of COPD management include elimination of symptoms, provision of improved health status, prevention and treatment of exacerbations, delay of disease progression and reduction in associated mortality (6,7). Evaluated from the patients' point of view, symptom control becomes the main determinant of treatment success based on its direct relation to health status, daily living activities, survival and exacerbation (8).

While COPD develops mainly in long-term smokers during 4th to 5th decade of the life, other risk factors such as exposure to certain dusts and chemicals in the workplace and use of biomass for indoor heating or cooking in poorly ventilated areas have also been defined (1,9,10). Nevertheless, COPD is also likely to be seen at younger ages among patients with serine protease inhibitor alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency as the most well-documented genetic risk factor of the disease (10,11).

The overall clinical picture of COPD has been explained in detail in the literature including several studies on the impact of disease on daily living and the general health status based on symptoms, severity, exacerbation, emotional state and even the patients' self perceived sense of physical functioning (12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23). However, there are only a few studies on patients' evaluation of this highly prevalent disease, despite the numerous disease-related functional impairments that effect daily living, significant symptomatic burden, and several screening surveys developed for use in daily clinical practice for the evaluation of disease (10,24).

As opposed to asthma, on which the public has gained increased awareness through information campaigns, COPD is still not a well-known disease and is often misunderstood, with a weak correlation between perception of patients and clinical evaluation of physicians concerning the impact of symptoms (3,25).

Absence or ignorance of symptoms at the initial stage of airflow obstruction has been associated often with a delay in the diagnoses and insufficient treatment of the disease (26). It gets more clear everyday, that the clinical and physiological output including dyspnea and health and functional status revealing extent of possible daily activities, have a significant role in evaluation of treatment response since evaluation of respiratory functions per se may not correctly illustrate the burden of COPD on patients nor the effects of treatment interventions (27,28). Therefore, an evaluation based on patients' self-reports on symptoms as well as health status has been considered to be an essential factor in determining the success of treatment (8).

Consequently, as in other chronic diseases, awareness of the impact of COPD on daily living is an important component of COPD management, predicted to contribute to tailor management to optimize patient benefit. In this regard, the present study was designed to determine the sociodemographic profile of patients, the impact of the disease on activities of daily living and the life style and needs of patients with stable COPD in Turkey, in order to gather data to guide our physicians on what issues to be aware of in the management of the disease.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population

A total of 497 patients with former or new-onset stable COPD were included in this national, multi-centered, cross-sectional observational study upon admission to one of 41 outpatient COPD centers across Turkey, between March and June of 2011, regardless of the disease severity. To better represent the real life profile, the centers were chosen from institutions with high number of COPD patients admitted. Having received a COPD diagnosis, being over 45 years old, smoking or having smoked (> 10 pack-years), having a forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio < 70% and having consented to participate were the main inclusion criteria for the patients admitting outpatient clinics.

The main criteria for exclusion included ongoing or recent (in the past three months) exacerbation in COPD (COPD symptoms worsening so that they lead to antibiotic and/or short term oral steroid treatment and/or hospitalization or an emergency visit); history of asthma and/or allergic rhinitis; lung cancer or bronchiectasis; lung fibrosis; interstitial lung disease; tuberculosis; a major respiratory disease like sarcoidosis; being enrolled in another clinical research or already having been enrolled in this study. An approval from the Ministry of Health General Directorate of Drugs and Pharmaceuticals was obtained prior to starting the study and each participant before enrollment gave an informed consent.

In this non-interventional study, the patient demographics (age, gender, level of education, smoking addiction), systemic comorbidities (diabetes, hyperlipidemia, depression, cardiovascular diseases, sleep disorders, chronic pain, etc) and COPD status [onset of illness, associated symptoms (dyspnea, wheezing, cough, sputum expectoration, chest tightness), stage of disease, regular medication use] data were collected during enrollment. Following the enrollment visit, via telephone follow-up within a month, patients were evaluated with respect to location of residence (city-town-village), marital status, living conditions, the numbers of admission to a physician, hospitalization and emergency admission for COPD in the last year, basic knowledge about COPD, daily living activities, the impact of COPD on these activities and their treatment expectations.

Assessment Variables

Assessment of the impact of COPD on daily activities, the primary evaluation parameter of the study, was calculated as the percent distribution of the patients with respect to answers (Yes/No/No Opinion) given to the patient survey questions on COPD's impact on daily life and identification of COPD dependent limited activities.

The secondary evaluation criteria including assessment of patients' sociodemographic profile, daily living conditions and needs, and treatment expectations were summarized as percentages based on patients' self-reports on related questions.

Statistical Analysis

The goal of this observational cross-sectional study was to enroll every stable COPD patient who visited any of the study centers within the enrollment period and met the enrollment criteria. The predicted number of patients per center was 10-20 for the enrollment period, so the expected total number of patients was set at 400. However, 497 patients were included in the study during the enrollment period.

Data were expressed as "mean (standard deviation; SD)", and percent (%) where appropriate. Descriptive statistics were provided for patient profile, COPD symptoms, symptom variability, impact of symptoms on morning activities, preventive measures and treatment approaches, and treatment expectations. Chi-square test was used for comparison of subgroups related to patient and disease characteristics and treatment. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics and Comorbidities

The mean age of the participants was 63.3 (9.3) years with 59.0% under the age of 65, and 89.9% of the participants were male. The majority (71.6%) of the patients were former smokers, while active smokers composed 28.4% of the study population with the mean (SD) pack-years smoked of 44.2 (26.7). Only 16.1% of the patients were illiterate while 83.9% reported graduation from at least a primary school.

Location of residence was city in 64.2% town in 23.5% and villages in 12.3%. The majority of the patients (93.2%) were married, 98% were living with their family and 75.9% stated that they could take care of themselves.

The mean (SD) number of dependants per patient was 2.2 (1.9) (median 2; min-max 0-15) with financial dependence in 2.1 (1.9) (median 2; min-max 0-15) persons per patient. Concerning occupational status, 13.7% of the patients were unemployed and 60.8% were retired and not working. The rest worked in various jobs, and 56.3% stated that they had enough income to provide for themselves.

Of the 497 patients enrolled, 297 (59.8%) had at least one comorbidity and the most common three comorbidities were cardiovascular diseases (34.6%), sleep disorders (21.3%) and gastrointestinal disorders (18.1%).

Past History and Symptoms of COPD

COPD diagnosis was made within the past year in 129 patients (26.0%) and a year or more ago in the remainder (74.0%). The mean (SD) COPD duration in patients with a diagnosis for at one year was 7.3 (6.5) years, and 45.3% had received COPD diagnosis within a year of onset of symptoms and the rest received it later. The mean (SD) duration of diagnosis was 5.4 (4.6) years in patients having symptoms for at least one year. The mean (SD) value of the latest FEV1 measurement was 52.1% (17.6) and the majority of the patients had moderate or severe COPD (46.3% and 33.8%, respectively).

Within the past year, the mean (SD) number of consults to a physician with an exacerbation was 4.9 (5.5), while the numbers of hospitalization and emergency admission were 0.4 (1.0) and 0.9 (2.4), respectively.

The main complaints identified by our patients were dyspnea (83.1%), cough (78.3%), sputum production (75.5%), wheezing (73.4%) and chest pain (64.2%).

COPD Knowledge Among the Patients

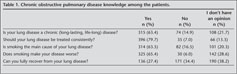

Majority of the patients were aware that COPD is a life-long chronic disease (63.4%), requiring continuous treatment (79.7%), caused mainly (63.5%) and also aggrevated by smoking (65.4%). The patients who believed that the disease could be cured completely composed 27.4% of the group, while 34.4% believed that it could not be completely cured; the remainder of the patients did not have an opinion on this matter (Table 1).

Impact of COPD on Daily Living of Patients

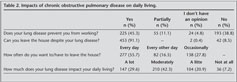

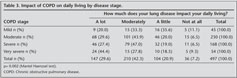

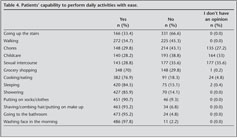

When the average time spent by patients on daily activities were evaluated with respect to age groups, the mean (SD) of the amount of time spent for laying down was only 9.3 (2.7) hours, followed by watching TV/listening to music with 5.0 (3.1) hours, time spent outside of house and work with 3.4 (2.8) hours, time spent at work/working 2.2 (3.8) hours, reading the newspaper/a book with 1.0 (1.3) hours, and chores with 0.6 (1.5) hours. Time spent watching TV/listening to music was significantly longer in the > 65 years old group than in the 45-65 years old group with means (SD) of 4.7 (3.0) and 5.5 (3.2) respectively (p< 0.001). While approximately 90% of the patients reported that the disease impacted daily living mildly, moderately, or significantly (20.9%, 42.3% and 29.6% respectively), 55.7% had to leave home everyday, 16.5% every other day and the rest occasionally (Table 2). There was a significant relation between the impact of COPD on daily living and the spirometric stage of the disease (p= 0.002; Table 3). Besides, more patients stated no capability to perform their effortful activities with ease (Table 4).

COPD Treatment

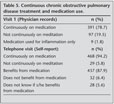

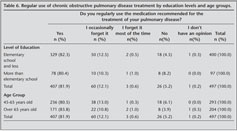

Based on the physician reports from the initial visit, 78.7% of the patients were continuously on medication and 1.8% was using medication when they had exacerbation (Table 5). Through the patient reports collected via telephone visit in the following month, it was recorded that 94.2% of patients were on medication continuously and 87.9% reported that they benefited from medication (Table 6). The patient reports also included that 81.9% of the patients used their medication regularly, 12.1% occasionally forgot their medications, 0.6% forgot medications for most of the time, 5.2% did not use medication regularly and 0.2% stated that they did not have an opinion on this matter (Table 6). There were no significant differences across different levels of education or age groups in terms of regular use of medication (Table 6).

Patient Expectations of COPD Treatment

When patients were asked what they would like to be able to do with more ease by means of treatment, the top 3 answers were being able to breathe (24.1%), walking (17.1%), and walking up stairs (11.7%). When they were asked what they would heal first in pulmonary disease patients if they were a doctor, 43.3% answered "shortness of breath" and 11.1% answered "coughing" (Table 7).

Discussion

The American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) define COPD as a preventable and treatable disease associated with the abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs to noxious particles and gases, characterized as an airflow limitation that is progressive and not fully reversible in terms of bronchodilatory response (29). Even though the airflow limitation is not fully reversible, this definition points out that the disease has treatable attributes in terms of preventing the deterioration in lung function and improvements in the clinical endpoints (6,30,31). The IBERPOC prevalence study showed that COPD is more likely to develop in males over 60-years, who have chronic bronchitis symptoms, live in the city and have smoking history (32). However, patients aged 55-64, who arrive at the clinic with wheezing, a prior chronic respiratory disease diagnosis, advanced deterioration in lung function and decrease in quality of life are more likely to be diagnosed as COPD (33). It is emphasized that the physicians rarely suspect COPD, and both the patients and the physicians usually unpredict this disease due to expecting cough and sputum complaints to be ordinary among smokers (33).

Even though it is known that COPD is observed mainly in older patients who are long-term smokers, the fact that 59.0% of the COPD patients in our study population were under the age of 65 may be related to certain factors including the age of smoking onset, amount of cigarettes smoked per day, being a sensitive smoker and encountering additional risk factors (9). Therefore, even if there is no shortness of breath, a simple spirometric examination in at-risk populations over the age of 40 might ensure early diagnosis of the disease.

On the other hand, the perception of COPD as a disease specific to the elderly (> 65 years old) among the public and the physicians may prevent the physician from making the correct diagnosis in younger patients who are highly symptomatic with cough, sputum production, and shortness of breath.

FEV1 and this volume's ratio to FEV1/FVC is a widely accepted measure of progressive airflow limitations. Recently, it has been emphasized that COPD requires effective monitoring in terms of symptoms, exercise tolerance, quality of life and adherence to treatment; as the course of COPD has been found to be associated with many factors at the cellular, organic, systemic, clinical and social levels in addition to the deterioration of the pulmonary functions (34,35). According to this, the latest mean (SD) FEV1 value of 52.1% (17.6), in our patients despite ongoing treatment, indicates failure of treatment in at least a portion of the study population or diagnosis at the later stages of the disease.

In accordance with the literature, 83.1% of the patients in our study population had dyspnea, 78.3% cough, 75.5% sputum production, 73.4% wheezing, and 64.2% had a feeling of tightness in the chest as symptoms (1).

Respiratory symptoms related to COPD show similar prevalence between males and females with percentages ranging from 6 to 61, but the presence of symptoms was reported to have a significant relation with lung function deterioration in male patients only (36). It is interesting that almost half of the COPD patients in our study group, the majority of whom are male, had a severe or very severe COPD diagnosis and a large portion (56.5%) of them had their diagnosis a year or more after the onset of symptoms.

Today, COPD is considered as a preventable and treatable disease. Quitting smoking, appropriate treatment of asthma, early diagnosis and keeping away from risk factors are effective in prevention. The appropriate COPD management, both stable and exacerbation periods, may provide the patients a higher quality of life, decrease in morbidity and mortality of the disease. Some of the important non-pulmonary systemic effects may contribute to the degree of severity of disease in COPD. Therefore, even with similar smoking and exposure levels, pulmonary function tests alone seem not adequate in the assessment of disease severity since different phenotypes of disease are likely due to "chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome" caused by pathologies like muscle loss, cardiovascular disease, osteopenia, depression, and chronic infections should be considered in COPD patients (37).

Health care providers and patients have a nihilistic attitude towards the early diagnosis and treatment of this disease because there are no pharmacotherapeutic alternatives to prevent the progression for the providers while the patients are reluctant or unenthusiastic in smoking cessation, and they adapt to the functional limitations to a certain degree (31).

Based on the BOLD study data, the prevalence of COPD over the age of 40 was 20%, and only 10% of the detected COPD cases had a prior COPD diagnosis made by a physician (38). Considering spirometric distributions the majority of the cases were reported to be in the mild-moderate group (44.79% in mild, 47.39% in moderate), and only 7.82% were reported to be in the severe-very severe group. In our study, approximately 45% of the patients were in the severe-very severe group. This shows that COPD patients seek help when the symptoms are significant and/or when they negatively impact the quality of life. As a matter of fact, identification of shortness of breath as the main complaint to be resolved by our patients supports this view. In addition, despite the fact that spirometry is a gold standard measurement in airway obstruction, spirometry devices are often not available in the clinical practice.

Questioning the health condition and the related quality of life of the patients should always be reported for its importance as an outcome in early diagnosis of COPD and predicting future hospital admissions and mortality (33). It is suggestive that with 90% of the patients' daily living is more or less affected by the disease and almost half of the patients provide for their family with 56% having an income just enough to make their living. 59% of the patients are under the age of 65 and have an average of two dependants, indicating that these patients are active in their lives, have responsibilities, and are not shut in.

Similarly, the belief in full recovery was identified only in 27.4% of our study population, while 34.4% of the patients considered that they will not fully recover, and the remainder had no an opinion on this matter which emphasize an important point concerning quality of life and course of the disease based on the direct relation between self perception of health status and survival (39).

In this respect, given the positive effect of the time spent outside the home on general health condition, and the preventive effect of physical activity on later hospital visits and severe exacerbations, realizing the strategies to increase physical activity level in COPD patients, in cooperation with them, will clearly have a positive impact on survival (34,40). Therefore, the most practical application to evaluate and follow-up on the exercise capacity of the COPD patients has been indicated to be the related questioning of patients on this issue during consultation (31).

COPD patients are less active compared to their healthy peers, and this lack of activity is the most distinct during the exacerbation periods of the disease (18). In accordance with this, walking up stairs and walking were the hardest daily activities in our study group, and were in the top 3 complaints seeking for therapeutic expectations following breathing.

In relation to impact of disease on normal activities of daily living, the most crucial point related to disease among COPD patients has been documented to be faster recovery of symptoms, particularly during periods of exacerbations (18). Similarly, treatment expectations of our patients were listed as breathing (24.1%), walking (17.1%) and walking up stairs (11.7%). Additionaly 43% of patients responded "shortness of breath" when asked what they would heal first in pulmonary disease patients if they were a doctor.

In the observational studies within the scope of primary health care, the patients were determined to have approximately two exacerbations per year and these exacerbations were reported to accelerate the deterioration in pulmonary functions and quality of life (18). Similarly, the average number of exacerbation related doctor consults within the past year for the patients in this study was 4.9, followed by 0.4 for hospitalization and 0.9 for emergency admissions.

As opposed to asthma, on which the public has gained awareness through information campaigns, COPD is not a well-known disease and is often misunderstood (3). There is usually a difference between the patients' perception and physicians' clinical evaluation concerning symptoms (25). Therefore, it is puzzling that the COPD patients and their care givers, who live with high burden of symptoms and related limited activities, social isolation and low quality of life, do not have the necessary level of informational, physical, emotional and social support opportunities (24). Therefore, knowing the therapeutic expectations of patients will clarify what really matters to them and lead the way for design of new clinical studies in this direction (18).

In addition, understanding therapeutic expectations of the patients was stated to be crucial in a past study based on tendency of patients to disregard their actual morbidities as well as significant discordance between self perception of disease severity and objectively determined actual severity of the disease (3).

The common features of pulmonary inflammation and systemic inflammation lead to high prevalence of comorbidities in COPD patients including mostly cardiovascular diseases (coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and other cardiovascular disease) along with lung cancer, musculoskeletal disorders, neurological disorders, ulcer and gastritis (41). The comorbidity profile in our patients which revealed evidence of comorbidities in 60% of the population with cardiovascular diseases in one third seems to be in accordance with the literature.

Diagnosis of COPD in 55% of the patients a year or more after the onset of symptoms raises concerns about the public knowledge of the disease. Increased knowledge levels about the disease among diagnosed patients may be associated with increased awareness following diagnosis.

Majority of the patients were aware that COPD was a chronic disease (63.4%), mainly caused (63.5%) and also aggravated (65.4%) by smoking. This is worth noting in relation to the main treatment goals of COPD, as a preventable and treatable disease, including control and reduction of symptoms, reduction of number and level of exacerbations, increasing the exercise tolerance by improving the health condition, slowing down the increased yearly pulmonary function loss and reducing the comorbidities and mortalities (1).

Smoking cessation and prevention of smoking in the first place are the most important measures in reducing COPD burden, not only at the individual level but also at the economic and social levels; of all the current treatments, smoking cessation has the most significant impact on reducing the yearly loss of FEV1 (31). In this respect, identification of former smoking in 71.6% of our patients is compatible with the finding of treatment compliance in 82% of our patients.

While 80% of our patients were aware of a continous treatment need in COPD, the report of the percentage of regular medication use in 78.7% of the study population by the initiation of the study and the increase of this rate to 94.2% based on patient reports obtained in the next month via to the phone visit emphasizes the use of more objective methods in testing the reliability of this subject.

On the other hand, the finding of a similar rate of regular medication use regardless of educational as well as age groups of patients in our study indicates indepence of regular medication device use among COPD patients from age and educational level of individuals.

Therefore, improvement of widely used guidelines developed by the BTS, the ATS/ERS and GOLD for COPD and development of compatible national guidelines seem crucial in order to minimize the heavy burden of the disease on the patients, the health care system and society (6,29,31,42). Even though clinical practice for management of COPD still lacks a monitoring parameter that is easy to apply, it is a reported necessity to have a direct measurement and an indirect assessment of parameters like increase in inflammation, symptoms, exercise tolerance, nutritional status, and exacerbations to follow the patients properly (31).

In conclusion, our findings indicate that a majority of COPD patients under treatment are younger than 65 years of age and are active in their daily lives. Considering the fact that diagnosed patients who are likely to be treated compose only 10% of the overall COPD population in our country, it can be predicted that onset of disease to date from mid-forties. The high rate of severe cases among COPD patients under treatment indicates a need for more effort on early diagnosis. An interesting finding of this study is that the treatment compliance rate is at 82% for the elderly and the less educated group. This finding points out that, in contrary to the common view, treatment compliance is independent of education level and age. This compliance might be caused by the positive impacts of the educational programs and the treatment results on patients' daily living. Based on our findings 91% of the patients go on an outing and more than two-thirds go grocery shopping. These findings are important indications that COPD patients are active participants in life who need accurate disease management with easy to use, portable medication devices to stay active. Therefore, availability of a portable and easy to use device seems to be important to enhance daily living.

AcknowledgEment

The study was funded by AstraZeneca Turkey. We thank to ?a?la ?sman, MD and Prof. ?ule Oktay, MD, PhD. from KAPPA Consultancy Traning Research Ltd. (Istanbul, Turkey) who provided editorial support funded by AstraZeneca Turkey.

REFERENCES

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Executive Summary 2006.

- Murray JL, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: global burden of disease study. Lancet 1997; 349: 1498-505. [?zet]

- Rennard S, Decramer M, Calverley PMA, Pride NB, Soriano JB, Vermeire PA, et al. Impact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subject's perspective of Confronting COPD International Survey. Eur Respir J 2002; 20: 799-805. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Walke LM, Gallo WT, Tinetti ME, Fried TR. The burden of symptoms among community-dwelling older persons with advanced chronic disease. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 2321-4. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Sullivan

SD, Ramsey SD, Lee TA. The economic burden of COPD. Chest 2000; 117(Suppl 2):

5-9.

[?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF] - Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004; 23: 932-46.[?zet] [PDF]

- GOLD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. 2009 [updated 2009; cited 2 June 2010]; Available from http://www.goldcopd.org/Guidelineitem.asp?l1=2&l2= 1&intId=2003.

- Stull

DE, Wiklund I, Gale R, Capkun-Niggli G, Houghton K, Jones P. Application of

latent growth and growth mixture modeling to identify and characterize

differential responders to treatment for COPD. Contemp Clin Trials 2011 Jul 6

[Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2011.06.004.

[?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF] - American Thoracic Society. Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152: 77-120.

- Cazzola M, Donner CF, Hanania NA. One hundred years of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-Republished article. Respir Med 2008; COPD Update 4: 8-25.[?zet]

- Stoller JK, Aboussouan LS. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Lancet 2005; 365: 2225-36. [?zet]

- Barnett M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a phenomenological study of patients' experiences. J Clin Nurs 2005; 14: 805-12.[?zet]

- Barr RG, Celli BR, Martinez FJ, Ries AL, Rennard SI, Reilly JJ Jr, et al. Physician and patient perceptions in COPD: the COPD Resource Network Needs Assessment Survey. Am J Med 2005; 118: 1415. [?zet]

- Ferrer M, Alonso J, Morera J, Marrades RM, Khalaf A, Aguar MC, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease stage and health-related quality of life. Ann Int Med 1997; 127: 1072-9.[?zet]

- Rutten-van M?lken MP, Oostenbrink JB, Tashkin DP, Burkhart D, Monz BU. Does quality of life of COPD patients as measured by the generic EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire differentiate between COPD severity stages? Chest 2006; 130: 1117-28. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Engstr?m

CP, Persson LO, Larsson S, Sulllivan M. Health-related quality of life in COPD:

why both disease specific and generic measures should be used. Eur Respir J

2001; 18: 69-76.

[?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF] - Jones PW. Quality of Life measurement for patients with diseases of the airways. Thorax 1991; 46: 676-82.[PDF]

- Miravitlles M, Anzueto A, Legnani D, Forstmeier L, Fargel M. Patient's perception of exacerbations of COPD-the PERCEIVE study. Respir Med 2007; 101: 453-60. [?zet]

- Kessler R, Stahl E, Vogelmeier C, Haughney J, Trudeau E, L?fdahl CG, et al. Patient understanding, detection and experience of COPD exacerbations: an observational, interview-based study. Chest 2006; 130: 133-42. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Haughney

J, Partridge MR, Vogelmeier C, Larsson T, Kessler R, Stahl E, et al. Exacerbations

of COPD: quantifying the patient's perspective unsing discrete choice

modelling. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 623-9.

[?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF] - Miravitlles M, Ferrer M, Pont A, Zalacain R, Alvarez-Sala JL, Massa F, et al. Effect of exacerbations on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease : a 2 year follow up study. Thorax 2004; 59: 387-95. [?zet] [PDF]

- Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, Cao Z, Ong KC, Eng P. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptoms burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 60-7.[?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Katula JA, Rejeski WJ, Wickley KL, Berry MJ. Perceived difficulty, importance, and satisfaction with physical function of COPD patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004; 2: 18. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Gardiner C, Gott M, Payne S, Small N, Barnes S, Halpin D, et al. Exploring the care needs of patients with advanced COPD: an overview of the literature. Respir Med 2010; 104: 159-65.[?zet]

- Ries AL. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on quality of life: the role of dyspnea. Am J Med 2006; 119 (Suppl 1): 12-20. [?zet]

- Anto JM, Vermeire P, Vestbo J, Sunyer J. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2001; 17: 982-94. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Cazzola

M, MacNee W, Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Franciosi LG, Barnes PJ, et al. Outcomes for

COPD pharmacological trials: from lung function to biomarkers. Eur Respir J

2008; 31: 416-69.

[?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF] - Jones P, Lareau S, Mahler DA. Measuring the effects of COPD on the patient. Respir Med 2005; 99 (Suppl B): 11-8. [?zet]

- Pauwels

RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS, GOLD Scientific Committee.

Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic

Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2001; 163: 1256-76.

[Tam Metin] [PDF] - van Schayck CP, Loozen JM, Wagena E, Akkermans RP, Wesseling GJ. Detecting patients at a high risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice: cross sectional case finding study. BMJ 2002; 324: 1370-4. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Van Schayck CP, Bindels PJE, Decramer M, Dekhuijzen PNR, Kerstjens HAM, Muris JWM, et al. Making COPD a treatable disease-an integrated care perspective. Respir Med 2007; COPD update 3: 49-56.

- Sobradillo Pena V, Miravitlles M, Gabriel R, Jime?nez-Ruiz CA, Villasante C, Masa JF, et al. Geographical variations in prevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD. Results of the IBERPOC multicentre epidemiological study. Chest 2000; 118: 981-9. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Miravitlles M, Ferrer M, Pont A, Luis Viejo J, Fernando Masa J, Gabriel R, et al. Characteristics of a population of COPD patients identified from a population-based study. Focus on previous diagnosis and never smokers. Respir Med 2005; 99: 985-95. [?zet]

- Garcia-Aymerich J, Gomez FP, Anto JM; en nombre del Grupo Investigador del Estudio PAC-COPD. Phenotypic characterization and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the PAC-COPD Study: design and methods. Arch Bronconeumol 2009; 45: 4-11. [?zet]

- Bellamy D, Bouchard J, Henrichsen S, Johansson G, Langhammer A, Reid J, et al. International primary care respiratory group (ICPRG) guidelines: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Prim Care Respir J 2006; 15: 48-57. [?zet]

- Watson L, Vonk JM, L?fdahl CG, Pride NB, Pauwels RA, Laitinen LA, et al; European Respiratory Society Study on Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Predictors of lung function and its decline in mild to moderate COPD in association with gender: results from the Euroscop study. Respir Med 2006; 100: 746-53.[?zet]

- Fabbri LM, Rabe KF. From COPD to chronic systemic inflammatory sendrome? Lancet 2007; 370: 797-9.

- Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gillespie S, Burney P, Mannino DM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007; 370: 741-50.[?zet]

- Nguyen HQ, Donesky-Cuenco D, Carrieri-Kohlman V. Associations between symptoms, functioning, and perceptions of mastery with global self-rated health in patients with COPD: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008; 45: 1355-65.[?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Miravitlles M, Llor C, Naberan K, Cots JM, Molina J. Variables associated with recovery from acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2005; 99: 955-65. [?zet]

- Wouters EF, Breyer MK, Rutten EP, Graat-Verboome L, Spruit MA. Co-morbid manifestations in COPD. Respir Med 2007; COPD Update 3: 135-51.

- The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. National clinical guideline on management of COPD in adults in primary and secondary care. Thorax 2004; 59 (Suppl 1): 1-232. [PDF]

Yaz??ma Adresi (Address for Correspondence):

Dr. Mehmet POLATLI,

Adnan Menderes ?niversitesi T?p Fak?ltesi,

G???s Hastal?klar? Anabilim Dal?,

AYDIN - TURKEY

e-mail: mpolatli@ttmail.com