?ran

s?n?r b?lgesindeki pulmoner t?berk?loz izolatlar?nda y?ksek d?zeyde

izoniazid

direnci katalaz-peroksidaz? kodlayan katG'deki multipl mutasyonla koreledir

Saeed

Z. BOSTANABAD1, Seyed Ali NOJOUMI2, Esmaeil JABBARZADEH3,

Mehdi SHEKARABEI3,

Hassan HOSEINAEI4, Mohammad K. RAHIMI5, Mostafa GHALAMI4,

Shahin POURAZAR DIZJI4,

Evgeni R. SAGALCHYK6, Leonid P. TITOV6

1 Islamic Azad University, Parand Branch, Biology and Microbiology Department, ?ran,

2 Pasteur Institute of Iran, ?ran,

3 Iran Medical University, Immunology Department, ?ran,

4 Masoud Laboratory, Microbiology Department, ?ran,

5 Islamic Azad University, Tehran Medical Branch, Microbiology Department, ?ran,

6 Belarusian Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, Clinical Microbiology, ?ran.

?ZET

?ran s?n?r b?lgesindeki pulmoner t?berk?loz izolatlar?nda y?ksek d?zeyde izoniazid direnci katalaz-peroksidaz? kodlayan katG'deki multipl mutasyonla koreledir

Bu ?al??man?n amac?, katG genindeki multipl mutasyonlar?n, n?kleotid de?i?ikliklerinin ?nemi ve ?ran'?n farkl? co?rafik b?lgelerinden rastgele toplanan primer ve sekonder aktif pulmoner t?berk?lozlu 42 hastan?n balgam?nda izoniazide y?ksek d?zeyde diren?li Mycobacterium tuberculosis izolatlar? ile ili?kisini ara?t?rmakt?. ?la? duyarl?l?k testi, CDC standart konvansiyonel metod kullan?larak yap?ld?. DNA ekstraksiyonu, katG gen amplifikasyonu ve DNA sekans analizi yap?ld?. ?zolatlar?n 34 (%80)'?nde katG geninde multipl mutasyon (2-5 mutasyon) saptand?. ?zoniazide y?ksek d?zeyde diren?li (M?K ?g/mL ≥ 5-10) sekonder t?berk?lozlu hastalarda daha s?k olmak ?zere, 315 (AGC?ACC), 316 (GGC?AGC), 309 (GGT?GTT) kodonlar?nda artm?? predominant mutasyon ve n?kleotid de?i?iklikleri saptand?. Ayr?ca, sekonder infeksiyonlu hastalarda daha s?k mutasyonu g?steren, 315, 316 ve 309 kodonlar?nda mutasyon kombinasyonlar? ve predominant n?kleotid de?i?iklikleri g?zlendi. Bu ?al??mada, multipl mutasyonlu izolatlar?n %62 (n= 21)'sinde, 315 (AGC?ACC), 316 (GGC?GTT), 309 (GGT?GGT) kodonlar?nda mutasyon kombinasyonlar? ile predominant n?kleotid de?i?iklikleri oldu?u bulundu ve bunun da izoniazide y?ksek diren?li (≥ 5-10 ?g/mL) sekonder infeksiyonlu hastalar?n izolatlar?nda daha s?k oldu?u saptand?.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Multipl mutasyon, M. tuberculosis, y?ksek d?zeyde izoniazid direnci.

SUMMARY

High level isoniazid resistance correlates with multiple mutation in the katG encoding catalase proxidase of pulmonary tuberculosis isolates from the frontier localities of Iran

Saeed

Z. BOSTANABAD1, Seyed Ali NOJOUMI2, Esmaeil JABBARZADEH3,

Mehdi SHEKARABEI3,

Hassan HOSEINAEI4, Mohammad K. RAHIMI5, Mostafa GHALAMI4,

Shahin POURAZAR DIZJI4,

Evgeni R. SAGALCHYK6, Leonid P. TITOV6

1 Islamic Azad University, Parand Branch, Biology and Microbiology Department, Iran,

2 Pasteur Institute of Iran, Iran,

3 Iran Medical University, Immunology Department, Iran,

4 Masoud Laboratory, Microbiology Department, Iran,

5 Islamic Azad University, Tehran Medical Branch, Microbiology Department, Iran,

6 Belarusian Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, Clinical Microbiology, Iran.

The aim of this study was to investigate the significance of multiple-mutations in the katG gene, predominant nucleotide changes and its correlation with high level of resistance to isoniazid in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates that were randomly collected from sputa of 42 patients with primary and secondary active pulmonary tuberculosis from different geographic regions of Iran. Drug susceptibility testing was determined using the CDC standard conventional proportional method. DNA extraction, katG gene amplification, and DNA sequencing analysis were performed. Thirty four (80%) isolates were found to have multiple-mutations (composed of 2-5 mutations) in the katG gene. Increased number of predominant mutations and nucleotide changes were demonstrated in codons 315 (AGC?ACC), 316 (GGC?AGC), 309 (GGT?GTT) with a higher frequency among patients bearing secondary tuberculosis infection with elevated levels of resistance to isoniazid (MIC ≥ 5-10 ?g/mL). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that the combination of mutations with their predominant nucleotide changes were also observed in codons 315, 316, and 309 indicating higher frequencies of mutations among patients with secondary infection respectively. In this study, 62% (n= 21) of multi-mutated isolates found to have combination of mutations with predominant nucleotide changes in codons 315 (AGC?ACC), 316 (GGC?GTT), 309 (GGT?GGT), and also demonstrated to be more frequent in isolates of patients with secondary infections, bearing higher level of resistance to isoniazid (≥ 5-10 ?g/mL).

Key Words: Multiple mutations, M. tuberculosis, high level resistant to izoniazid, Iranian isolates.

Isoniazid is a first-line chemotherapeutic drug used in tuberculosis (TB) therapy (1,2,3). Resistance to isoniazid is associated with a variety of mutations affecting one or more genes such as that encoding catalase peroxidase (katG) (4,5). The katG gene is the most commonly targeted region of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome with the majority of mutations occurring in codon 315 in 30-90% of isoniazid-resistant strains depending on geographical distribution (6,7). Izoniazid resistance is the most frequently associated with a single mutation in katG gene, a gene that encodes catalase peroxidase enzyme in M. tuberculosis (8). Most isoniazid-resistant M. tuberculosis strains have not been reported to have a high proportion of katG deletions suggesting the need to more precisely analyze the structure of the katG gene in the resistant organisms. Further studies have revealed that katG gene deletions are very rare and this requires more detailed analysis of the katG its structure (4,5,9). Several groups have recently reported that many isoniazid-resistant strains contain missense and other types of mutations (4). Mutations at the Ser315 codon of katG have been reported to be associated with high-level of isoniazid resistance (10). Resistance to isoniazid has a second degree of magnitude in Iran, and combinations of mutations conferring M. tuberculosis resistance to isoniazid have been reported to be more common in the multi-drug resistance tuberculosis (MDR-TB) than in mono-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates, suggesting that isolates develop resistance to isoniazid by a stepwise accumulation of mutations (5,11).

In this study, we investigate the significance of multiple-mutations in the katG gene, its correlation with predominant nucleotide changes, and high level of resistance to isoniazid in 42 isolates of M. tuberculosis collected from patients with primary and secondary active pulmonary tuberculosis from different geographic regions of Iran.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Mycobacterial Strains

One hundred and sixty three M. tuberculosis were isolated from sputa of patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis collected from various geographic regions of Iran (Tehran, Zabol, Kermanshah, Mashad, Tabriz) from December 2007 to May 2008. Patients' history of tuberculosis, gender, clinical symptoms, radiography, tuberculin skin test (TST), etc. was recorded before collection of specimen. All isolates were cultured on Lowenstein-Jensen solid medium and grown colonies were identified to the species level using TCH (2-thiophene carboxylic acid) and PN99B (paranitrobenzoic acid) selective media using CDC standard biochemical procedures (12). Four sensitive isolates were selected and used as controls.

Susceptibility Testing

Anti-microbial drug susceptibility testing (AMST) was performed using the CDC standard conventional proportional method rifampicine (Rif) 40 ?g/mL, isoniazid (INH) 2 ?g/mL, ethambutol (EMB) 2 ?g/mL, ethionamide (ETH) 20 ?g/mL, streptomycin (SM) 4 ?g/mL, and kanamycin (K) 20 ?g/mL were used in slants and in addition to breakpoint concentrations for isoniazid 0.1 ?g/mL, and rifampicin 2.0 ?g/mL were also used in the BACTEC system (12). Four sensitive M. tuberculosis isolates and an H37Rv strain were used as negative controls. Mutations in the katG gene were identified on 42 isoniazid resistant isolates by sequencing methods and AMST was performed following sequencing to confirm resistance using different concentrations of isoniazid 2 5 and 10 ?g/mL in the slant proportional method (12).

Standard PCR Identification and

katG Gene Amplification

DNA extraction was done by Fermentase kit (K512), and DNA purification by Fermentase kit (k513-Graiciuno 8, Vilnius 2028, Lithuania). DNA extracted from M. tuberculosis CDC1551, Mycobacterium H37RV strains and from four sensitive isolates of M. tuberculosis was used as the negative control. A 209bp and 750bp segment of the katG gene were amplified by PCR using the following synthetic oligonucleotide primers katG F 5-GAAACAGCGGCGCTGGATCGT- 3, katG R 5- GTTGTCCCATTTCGTCG GGG-3 for 209 bp and katG F 5 CGGGATCCG CTGGAGCAGATGGGC-3 and katG R 5-CGGAATTCCAGGGT GCGAATGACCT-3 for the 750bp fragment (13). PCR was carried out in 50 ?L tube containing 2 ?L KCl, 2 ?L Tris (pH 8.0), 1.5 ?L MgCl2, 5 ?L dNTP, 1UTaq polymerase, 27 ?L water (DDW molecular grade), 20 pmol of each primer and 6-10 ?L of DNA template. The following thermocycling parameters were applied: initial denaturation at 95?C for 5 min; 36 cycles of denaturation at 94?C for 1 min; primer annealing at 56?C for 1 min; extension at 72?C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72?C for 10 min. The PCR product was amplified and purified again and controlled on the gel electrophoresis for purified segment. The final purified mycobacterial DNA obtained and was used for sequencing.

DNA Sequencing

The 209 bp and 750 bp fragments of the katG gene were amplified by PCR using forward or reveres primers mentioned above; 33 cycles of C for 45 sec; extension C for 30 sec; primer annealing at 48 denaturation at 94?C for 4 min. at 60 katG gene fragments were sequenced by using an Amersham auto sequencer and Amersham Pharmacia DYEnamic ET Terminator Cycle Sequencing Premix Kits.

Purified DNA of the katG fragment obtained from M. tuberculosis CDC1551, Mycobacterium H37RV strains and from four sensitive isolates was used as negative controls.

Analyzing of DNA Sequencing

Alignment of the DNA fragments (katG) were carried out using the MEGA and DNAMAN software (Gen bank PUBMED/BLAST) and was compared with the standard strains of CDC1551, H37RV and M. tuberculosis 210. The Blast 2 sequencing computer program was used for DNA sequence comparisons (http://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/BLAST/). Alignment of the DNA fragments (katG) was carried out with MEGA 3.1 software (www.megasoftware.net/mega3.1/) and obtained data were analyzed and edited with DNAMAN software.

Definitions

In this study, primary cases (never-treated patients-new cases) refer to patients who did not have a previous history of tuberculosis disease or medical treatment. Secondary cases (previously treated patients) demonstrated a previous history of tuberculosis disease in their medical records

RESULTS

Mycobacterial Strains and Susceptibility

From 163 isolates, 42 were found to be resistant to isoniazid (100%), rifampicine (90%), streptomycin (90%), and ethambutol (28%). Mono-resistance to isoniazid was observed in 4 isolates (9.5%). In total, 42 isoniazid resistant and 121 sensitive isolates were identified.

Mutations were not detected for the four sensitive isolates to isoniazid in 209 bp and 750 bp regions of katG gene. Mutations were observed in affected codons 305, 306, 307, 309, 314, 315, 316, 321, 328 in 209 bp fragment and in 357, 454, and 463 of the 750 bp fragment of katG gene. In 40 isolates four types of mutations were identified in codon 315: AGC?ACC (n= 36) 80%, AGC?AGG (n= 1) 2.3%, AGC?AAC (n= 2) 4.7% and AGC?GGC (n= 1) 2.3%. One type of mutation was found in codon 316: GGC?AGC (n= 18) 41.4%, and in 15 isolates four types of mutations were demonstrated in codon 309: GGT?GTT (n= 7) 16.1%, GGT?GCT (n= 4) 9.2%, GGT?GTC (n= 3) 6.9%, GGT?GGG (n= 1) 2.7% (Table 1).

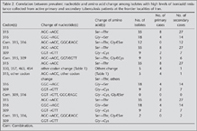

Predominant nucleotide changes were observed in 40 isolates as 315 (AGC?ACC) indicated to evolve (n= 28) 77% from secondary and (n= 8) 23% from primary cases, 316 (GGC?AGC) in which 77% (n= 14) from secondary and 23% (n= 4) from primary, and 309 (GGT?GTT) that 71% (n= 5) from secondary and 29% (n= 2) from primary cases, respectively (Table 2). Out of 105 mutations, predominant nucleotide changes were seen in codon 315 AGC?ACC (Ser?Thr) 36% (n= 40), 316 GGC?AGC (Gly?Ser) 17.7%, and in codon 309 GGT?GTT (Cys?Phe) 6.3% (n= 7) (Table 1, Table 2).

Six isolates 14% (n= 6) were identified from secondary cases with predominant mutations observed in three codons 315, 316 (100% each) and in codon 309 (67%, n= 4), including non predominant mutation observed in 2 (33%) isolates of codon 309 (Table 2).

Twenty-six (62%) isolates demonstrated multiple mutations in at least two of the three codons (309, 315, 316) with predominant nucleotide changes in which nucleotide combination 315 (AGC?ACC), 316 (GGC?AGC) n= 12 (46%) all differentiated from secondary cases, and nucleotide combinations of 315 and 309 in which 315 (AGC?ACC) n= 9 (34.5%) was identified in 6 (23%) secondary and 3 (11.5%) primary cases, and a 309 mutation (GGT?GTT) found in secondary case (Table 2). Nucleotide combination in codon 316 and 309 were not found in primary or secondary cases (Table 2). Nucleotide combinations of 315 with others codons were observed in (n= 4) 15% of patient isolates including 3 secondary cases and 1 primary case (Table 2).

In two isolates, 2 types of mutations were found in codon 357 GAC?CAC and GAC?AAC. In addition two mutations which were also observed in codons 463 CGG?CTG and 454 GAG?CGA were found in secondary cases and did not correspond to high level resistance to isoniazid (MIC ≤ 2 ?g/mL).

Isolates bearing a single mutation n= 8 (19%), double mutations n= 17 (40.46%), triple mutations n= 9 (21.42%), four mutations n= 4 (9.5%) and five mutations n= 4 (9.5%) were also observed among 42 resistant isolates (Table 1).

Silent Mutations

Three silent mutations were identified in four isolates in codons 306 (CCG?CCC), 309 (GGT?GGG) and 314 (ACC?ACG). These silent mutations did not show any effect on the susceptibility testing pattern (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Isoniazid resistance is a surrogate marker for MDR M. tuberculosis (rifampin and isoniazid resistance) and is the result of mutation within certain region of the katG gene which encodes the catalase proxidase. It is important to understand the correlation of the clinical states of patients with tuberculosis to mutations and high resistance levels to isoniazid to determine wether the patients are initially infected with the MDR M. tuberculosis strain or whether the emergence of MDR M. tuberculosis was due to inadequate or inappropriate antibiotic treatment that resulted in the acquisition of mutations and antibiotic resistant. The known genes related to isoniazid-resistant are katG, inhA, ahpC, kasA (14). Several investigators have reported that M. tuberculosis resistance to isoniazid corresponds to amino acid changes in codon 315 (3,6,10). In our study, we have observed 95% of all isoniazid resistant isolates (n= 40) showed mutations in codon 315. Whereas 40% of all mutations (n= 105) conferring different types of nucleotide changes were found to be in codon 315: AGC?ACC (Ser?Thr) as predominant nucleotide changes 36%, and AGC?AGG (Ser?Arg) 0.9%, AGC?AAC (Ser?Asn) 1.8%, AGC?GGC (Ser?Gly) 0.9% were observed as non predominant. One type of mutation was found in codon 316: GGC?AGC (n= 18) 41.4%, and in 15 isolates four types of mutations were demonstrated in codon 309: GGT?GGT (n= 7) 16.1%, GGT?GCT (n= 4) 9.2%, GGT?GTC (n= 3) 6.9%, GGT?GGG (n= 1) 2.7% (Table 2). Predominant mode of acquisition of resistance via katG alterations is the selection of particular mutations that decrease the catalase activity but that maintain a certain level of the peroxidase activity of the enzyme in viable INH-resistant (INHr) organisms. The above data correlate with our findings that such mutations were found to be up to 85% of the INHr clinical isolates with decreased catalase activity. These mutations appear to provide the optimal balance between decreased catalase activity and a sufficiently high level of peroxidase activity in KatG (15).

In this study, nucleotide changes in codon 315: AGC?ACC (n= 36) 80%, 316: GGC?AGC (n= 18) 41.4% and 309: GGT?GTT (n= 7) 16.1% were more predominantly observed among isolates collected from secondary infection cases, and correlating to a higher frequency level of resistance to isoniazid MIC ≥ 5-10 ?g/mL. This observation correlate with other studies reported that multi-drug resistance was found among 14% of the amino acid 315 mutants and 7% of the other INH-resistant strains (p> 0.05) (10), and reported that amino acid 315 mutants lead to secondary cases of tuberculosis as often as INH-susceptible strains (10). Distribution of isoniazid resistance associated mutations reported by other investigators to be different in isoniazid mono-resistant isolates when compared with multi-drug-resistant isolates, significantly fewer isoniazid resistance mutations observed in the isoniazid mono-resistant group and also mutations in katG315 were significantly more common in the multi-drug resistant isolates (16). Conversely, mutations in the inhA promoter were significantly more common in isoniazid mono-resistant isolates (16). It has been suggested that some drug resistance associated mutations occur at higher frequencies in MDR M. tuberculosis than in mono-isoniazid resistant clinical isolates (16). Whereas our data demonstrate that only 9.5% (n= 4) mono-resistant, 90% (n= 38) multi-drug resistant and 26 (62%) of isolates with multiple mutation conferring high level of resistance to isoniazid (MIC ≥ 5-10 ?g/mL). Unfortunately, we have not completely examined the role of inhA promoter among mono and multi-drug resistant conferring multiple mutations in this study. Other studies reported that INHr strain showed a mutation in the katG gene in codon 314 as ACC?CCC (Thr?Pro) which has not been previously defined (17). However, in this study we found mutations in nearby similar segment of the katG gene in codons 309 and 316 which have very seldom been reported and associated with secondary MDR cases.

Our findings are in agreement with similar data reported in Lithuania where 95% of strains displayed mutation in codon 315 of the katG gene with the predominance of codon substitution AGC?ACC (Ser?Thr) (90%) (Bakonyte et al. 2003). However, we could not identify the mutation of AGC?ACA (Ser?Thr) which has been reported in Lithuania (5). In Poland 90% mutations are in the 315 AGC codon which corresponds to 5 types of mutations (ACC, ACT, ACA, AAC, and ATC) and resemble similar pattern of changes with our data including nucleotide ACC and AAC. However contrary to the data from Poland we did not observe nucleotide changes of ACT, ACA and ATC in Iran (18). In Russia the highest proportion of nucleotide changes (70%) have been reported to be in the katG codon 315 AGC?ACC which is similar and in agreement with our data (2). Mutations at the Ser315 codon of katG have been reported to be associated with high-level isoniazid resistance (10) which is similar to our findings in 8 (19%) isolates bearing a single mutation at codon 315 and conferring resistance to isoniazid (MIC ≥ 5-10 ?g/mL). This data suggests the alternative or complementary explanation that strains with mutations at codon 315 are more likely to gain increased resistance (10).

In our study, four types of mutations were detected in codon 309: GGT?GTT (Cys?Phe) 6.3%, GGT?GCT (Cys?Ser) (3.6%), GGT?GTC (Cys?Phe) (2.7%), GGT?GGG (Cys?Thr) (0.9%). Additionally, we identified a mutation in codon 316 GGC?AGC (Gly?Ser) (14.4%) which has not been reported previously. In this study, 75% of all isolates resistant to isoniazid (n= 42) demonstrated multiple types of mutations in codons 309 (n= 15, 34%) and 316 (n= 18, 41.4%) which might represent a second importance of mutations present in isolates of patients bearing secondary infection in Iran which has not been reported previously. In six isolates (14%) bearing a combination of multiple mutations in three codons (309, 315 and 316) and in 26 (61.9%) isolates that demonstrated having combinations of multiple mutations (in at least two of the three mentioned codons) were found to be MDR isolates having high frequency levels of resistance to isoniazid MIC ≥ 5-10 ?g/mL. These finding indicate correlation of high level resistance due to mutation in codon 315 which has been shown by other authors (16). Higher frequency of combination of multiple mutations in katG gene (codon 315, 309 and 316) has not been previously reported in patients with secondary infection (Table 1, Table 2). One explanation can be postulated that high population rate of alcoholism and incomplete treatment can be the cause of mutations. The other logical reason could be explained that high rate of immigrant transits of patients from high TB incidence areas like India, Afghanistan and China to Europe via center of eastern Europe (Iran) which can cause distribution, circulation, and interaction of numerous different molecular types of tuberculosis cases might lead to such combination of rare mutations. Other researchers have suggested that isolates develop resistance to isoniazid by a stepwise accumulation of mutations, which may be important for achieving the higher level of resistance or maintaining virulence in a human host. Inadequate prolonged treatment results in an accumulation of mutations, ultimately leading to katG and/or inhA mutations in virtually all strains. This finding is in agreement with our data regarding higher frequency of predominant nucleotide changes among secondary case infections. In contrast to our findings other investigators have not reported the association of multiple mutations and predominant nucleotide changes with high level resistance among patients with secondary infection cases.

In 2 isolates mutations were not detected in the 209bp fragment, therefore we sequenced the larger 750 bp fragment of katG gene for all isolates and have identified mutations in codons 463, 357, and 454, 357, which may indicate that this type of mutation is non-predominant colon in Iran when compared with neighboring countries (4,6,13,19). Other investigators have reported no silent mutations detected in the katG gene (9,20,21). Whereas, in our strain set three silent mutations (2.7%) in codons 306 (CCG?CCC), 309 (GGT?GGG) and 314 (ACC?ACG) were demonstrated which had no effect on the susceptibility testing pattern. The high percentage of double mutations found among the isolates of Iran clearly differed from the lower prevalence of double mutations in other studies (18,22,23,24). A prominent finding of this study was the high frequency of double (40.47%), triple (21.42%), quadruple (9.5%) and five nucleotide mutations (9.5%) occurring in separate codons indicating predominant nucleotide changes in codons 315, 316 and 309 to be more prevalent among secondary cases (Table 1).

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a correlation between the multiple mutations of the katg gene and the prevalent nucleotide changes in codon 309, 315 and 316. Notably, in multiple isolates bearing double, triple, quadruple and quintet mutations predominantly identified to be from secondary infection cases, high levels of isoniazid resistance (MIC ≥ 5-10 ?g/mL) were seen. These data illustrate the need for further investigations to develop a more rapid and specific assay for the detection of MDR M. tuberculosis to be used as a screening method in areas where tuberculosis is highly endemic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank our colleagues in the Iranian Institutes of Pulmonology and Tuberculosis for samples collected. This study was a joint research project with Islamic Azad University- parand branch and Belarusian Research Institute for Epidemiology and Microbiology, Minsk.

CONFLICT of INTEREST

None declared.

References

- Eltrigham IJ, Drobniewski FA, ManganJA, et al. Evaluation of reverse transcription-PCR and a bacteriophage-based assey for rapid phenotypic detection of rifampin resistance in clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 11: 3524-7. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Mokrousov I, Narvskaya O, Otten T, et al. High prevalence of KatG Ser315Thr substitution among isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from northwestern Russia, 1996 to 2001. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46: 1417-24. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Herrera-Leon L, Molina T, Saiz P, et al. New Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49: 144-7. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Abate G, Hoffner SE, Thomsen VO, Mi?rner H. Characterization of isoniazid-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on the basis of phenotypic properties and mutations in katG. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2001; 20: 329-33. [?zet]

- Bakonyte D, Baranauskaite A, Cicenaite J, et al. Molecular characterization of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates in Lithuania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003; 4: 2009-11. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Mokrousov I, Otten T, Filipenko M, et al. Detection of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains by a multiplex allele-specific PCR assay targeting katG codon 315 variation. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 5: 2509-12. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Leung ET, Kam KM, Chiu A, et al. Detection of katG Ser315Thr substitution in respiratory specimens from patients with isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis using PCR-RFLP. J Med Microbiol 2003; 52: 999-1003. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Dobner PS, Rusch-Gerdes G, Bretzel K, et al. Usefulness of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genomic mutations in the genes katG and inhA for the prediction of isoniazid resistance. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1997; 1: 365-9. [?zet]

- Kiepiela P, Bishop KS, Smith AN, et al. Genomic mutations in the katG, inhA, and ahpC genes are useful for the prediction of isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Kwazulu Natal, South Africa. Int J Tuber Lung Dis 2000; 80: 47-56. [?zet]

- Van Soolingen, D, de Hass PE, van Doom HR, et al. Mutations at amino acid position 315 of the katG gene are associated with high-level resistance to isoniazid, other drug resistance, and successful transmission Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Netherlands. J Infect Dis 2000; 182: 1788-90. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Titov LP, Zaker Bostanabad S, Slizen V, et al. Molecular characterization of rpoB gene mutations in rifampicine-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from tuberculosis patients in Iran. Biotechnol J 2006; 24: 1447-52. [?zet]

- Kent PT, Kubica GP. Public Health Mycobacteriology, a Guide for the level III laboratory, CDC, US. Department of Health and Human Service Publication no. (CDC) 86-216546, Atlanta 1985; 21-30.

- Telenti A, Honore N, Bernasconi C, et al. Genotyping assessment of isoniazid and rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a blind study at reference laboratory level. J Clin Microbiol 1997; 35: 719-23. [?zet] [PDF]

- Zheltkova EA, Chernousova LN, Smirnova TJ, et al. Molecular genetic typing Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated from patents in the samapa region by the restriction DNA fragment length polymorphism. Zh Microbial (Moscow) 2002; 5: 39-43. [?zet]

- Ramaswami S, Musser JM. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Update. Tuberc Lung Dis 2002; 79: 3-29. [?zet]

- Hazbo? MH, Brimacombe M, Bobadilla del Valle M, et al. Population genetics study of isoniazid resistance mutations and evolution of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 50: 2640-9. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Ozturk CE, Sanic A, Kaya D, CeyhanI. Molecular analysis of isoniazid, rifampin and and streptomycin resistance in mycobacterium isolates from patients with tuberculosis in Duzce Turkey. Jpn J Infect Dis 2005; 8: 309-12. [?zet] [PDF]

- Sajduda A, Brzostek A, Poplawska M, et al. Molecular characterization of rifampine-and isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated in Poland. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 2425-31. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Zaker SB, Titov LP, Bahrmand AR, Taghikhani M. Genetic mechanism of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance to antituberculsis drugs, isoniazid and rifampicine. Journal Daklady of National Akademia Science Iran 2006; 50: 6; 92-8.

- Bobadilla-del-Valle M, Ponce-de-Leaon A, Arenas-Huertero C, et al. rpoB gene mutations in rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis identified by polymerase chain reaction single-stranded conformational polymorphism. Emerg Infect Dis 2001; 7: 1010-3. [?zet] [PDF]

- Garcia M, Vargas JA, Castejon R, et al. Flow-cytometric assessment of lymphocyte cytokine production in tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2002; 82: 37-41. [?zet]

- Silva MS, Senna SG, Ribeiro MO, et al. Mutations in katG, inhA, and ahpC Genes of Brazilian isoniazid-resistant isolates Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 2003; m9: 4471-44. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- van Doorn HR, Claas EC, Templeton KE, et al. Detection of a point mutation associated with high-level isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by using real-time PCR technology with 3'-Minor Groove Binder-DNA Probes. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41: 4630-5. [?zet] [Tam Metin] [PDF]

- Zaker Bostanabad S, Titov LP, Bahrmand AR. Frequency and molecular characterization of isoniazid-resistance in katG region of M.D.R isolates from tuberculosis patients in southern endemic border of Iran. Infection Genetics and Evolution 2008; 1: 11-9. [?zet]

Yaz??ma Adresi (Address for Correspondence):

Dr. Saeed Z. BOSTANABAD,

Parand New City TEHRAN - IRAN

e-mail: saeid1976@mail.ru